India plundered – Part IV

Was Aurangzeb really all that terrible?

RN Bhaskar — 21 September 2020

==============

The other parts of this series can be found at

http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/09/the-plunder-series/

==========================

History books in India talk darkly about Aurangzeb, the Mughal emperor. Demagogues rail against him. Stories about him are used to demonise a community. They even compelled the government to change the name of one of the most prominent roads in the country’s capital.

But look at facts as they stand today. It is then that you realise that Aurangzeb’s crimes fade into insignificance when compared to the acts of commission and omission by the central and state governments in India. Like Aurangzeb, they too have attempted to emasculate Hindus.

Aurangzeb did this more directly – by imposing the obnoxious Jizia tax on Hindus. Indian governments have been more devious. They have sought to make these collections indirectly – through temple trusts.

Some governments do this by taxing temples by taking a percentage of religious donations offered by devotees (J Sai Deepak, Our temples don’t belong to us – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js936p_cvTE&feature=youtu.be). Many others have just usurped management control over temple trusts.

The lust for money has been so great that the state has opted to deny the largest religious community in India the sagacious guidance of its religious leaders. It merely pays lip-service to protecting Hindus – like the justification for the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

True, the seer of Tirupati-Tirumala trust remains the titular head of the temple complex and its devotees. But he is told that the funds belong to the government. The government decides how the money should be spent — even on paying the priests and other staff in the temple complexes. The religious leaders can’t even decide who in the community should be rewarded or encouraged. That too is the government’s decision.

Clearly, the politicians and bureaucrats have either forgotten or overlooked the simple fact that community vision goes beyond a few hundred years. The vision of most politicians and bureaucrats seldom goes beyond a decade.

Clearly, the politicians and bureaucrats have either forgotten or overlooked the simple fact that community vision goes beyond a few hundred years. The vision of most politicians and bureaucrats seldom goes beyond a decade.

By taking away the purse strings of temple trusts, successive governments have actually made Hinduism lose its vision. And this vacuum is filled up with self-styled godmen. Each of them has a political backing or the support of a mentor close to politicians. These godmen are allowed to usurp land, collect money which often remains unaudited, and even indulge in acts which would normally have resulted in criminal charges against common folk.

It is only when these godmen lose political favour, or when public mood turns against them, that action is ostensibly taken against them. That could explain the moves against Asaram or Ram Rahim (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/09/what-makes-a-ram-rahim-thrive-inindia/). But the cases against them are allowed to drag on. That gives authorities the ability to persuade witnesses to recant, or to create new evidence, or to make people forget the case itself.

Consequently, temple trusts remain under government audit scrutiny. But politician-favoured godmen escape any such scrutiny.

How else could you explain the government’s much publicised moves against a person like Vijay Mallya, but the benign manner (and the media silence) that surrounds the audacious escape of self-styled godman Nityanand, accused of rape charges, forex violation and of absconding police summons, To top it all, Nityanand claims to have purchased an island that he cheekily calls the kingdom of Kailasa (after the legendary abode of one of the Hindu deities). He has also created a Reserve Bank of Mount Kailasa, and brought out his own currency (swarn-mudra).

Mallya, on the other hand, actually created jobs. He was a wealth generator. He paid government taxes. He has also offered to repay all that he owes to banks, even though they are under dispute. Mallya was denied the right to sell Kingfisher as a going concern, which could have fetched some money. Now it is a dead asset, worth almost nothing.

Nobody gained. Not the government. Not Mallya. The money was eventually billed to the taxpayers of India.

Thus, there is plunder of temple trusts. There is indirect plunder through self-styled godmen. And there is value destruction too, as assets are allowed to wither away.

India is where self-styled godmen are allowed to get away lightly for crimes and omission and commission. Yet, out-of-favour wealth generators are hounded and pilloried. The original seats of learning — with a legacy of over five thousand years — remain desecrated by government appointed officials. People forget that they were the biggest galvanisers of community wealth; the binding force behind the concepts of Hinduism. Many government officials are today themselves accused of corruption and mismanagement of funds. If this is not plunder – on a scale much bigger than ever envisaged by Aurangzeb — what else could it be?

How rich are Hindu temples?

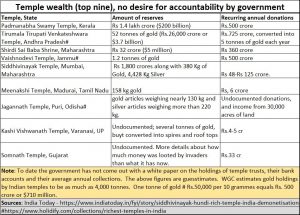

The government, even though it has access to this information, has not yet come out with a white paper on the amount of gold or cash lying with temple trusts, or the amounts they earn by way of donations each year. But if one goes by 2015 estimates of the World Gold Council in a report titled “India’s gold market: evolution and innovation” – (appendix 3 – Page 86, India’s above ground stocks), Hindu temples could be holding as much as 4,000 tonnes of gold which by current valuations of Rs.50,000 per 10 grammes, would be worth Rs.20 lakh crore ($286 billion).

But, as the report clarifies, “1,000 tonnes might have been accrued before 1968 (donations by erstwhile rulers of once-upon-a-time princely states), which means between 1,000 tonnes and 3,000 tonnes was given to religious institutions by private individuals”

The sheer paucity of data is evident elsewhere as well. For instance, an India Today report on the wealth of temples does not have adequate data on the top 10 temples. Thus, the table alongside, had to source some information from elsewhere. Even then they are informed estimates.

The willingness of state and central governments to take control of trust funds, coupled with the reluctance to be transparent about amounts under their control, and the amounts garnered each year, leave analysts with a very uncomfortable feeling – temple trust takeover is nothing but a grab for money and power without accountability.

The origins

The origins of the law permitting governments to control temple trusts and funds appears to go back to 1811, That was when Colonel Munroe from the East India Company demanded a tribute of from the Queen of Travancore to protect her empire (https://www.pgurus.com/it-all-started-in-1811-when-a-colonel-munro-of-east-india-company-demanded-rs-8l-as-tribute-from-the-queen-of-travancore/) . When the Queen of Travancore expressed her inability, Munroe suggested taking control of the temples with their wealth of income and properties.

The origins of the law permitting governments to control temple trusts and funds appears to go back to 1811, That was when Colonel Munroe from the East India Company demanded a tribute of from the Queen of Travancore to protect her empire (https://www.pgurus.com/it-all-started-in-1811-when-a-colonel-munro-of-east-india-company-demanded-rs-8l-as-tribute-from-the-queen-of-travancore/) . When the Queen of Travancore expressed her inability, Munroe suggested taking control of the temples with their wealth of income and properties.

When Munroe became the Regent Diwan of Travancore, he implemented this meticulously, which paved the way for handcuffing the temples. When East India Company was taken over by the British government, along with it came the control of temples by revenue and charitable institutions departments of the British government. Some of the temples were even alienated from the properties they controlled.

This led to the promulgation of the Madras Religious and Charitable Endowment Act which later became The Madras Hindu Religious & Charitable Endowment Act. (the Madras Presidency then was large covering parts of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Kerala as well). The Hindus then, as even now, were largely unorganised, even fragmented, as a religious community. They were thus mostly unaware of the potential dangers of this Act, and remained indifferent.

Gradually, similar legislations were enacted in other parts of the country. This Act had extensive provisions. In territories where the religious trusts were more organised – like the Devaswoms of South India – they were brought under tighter control by the British government.

A colonial legacy continues

When India became independent, these laws regulating the Devaswoms survived (https://www.organiser.org/Encyc/2020/6/12/Hindu-Temple-money-for-Secular-Kerala-government-Swami-Chidananda-Puri.html). Even when India became a Sovereign Democratic Republic in 1950, the Devaswoms continued to remain under the control of the (independent) Indian government. Places of worship for other religions could not be touched, because the Constitution offers them the protection of being Minorities (some believe that the hidden intent of the common civil law is to remove this minority protection that these communities enjoy). Thus Hindu temple trusts got pilloried by default. Aurangzeb must be smiling in his grave.

Today, the government has every right to acquire Hindu temples and it already has control of more than 250,000 temples in Karnataka, more than 400,000 temples in Andhra and similarly lakhs of temples in other states.

According to this law, all the revenues generated by the temple (including Hundi funds) will go to the government (not the temple priests/heads) and it is the prerogative of the Government to decide how much of this revenue will be returned to the temples for their maintenance (http://guruprasad.net/posts/really-happens-money-temple-hundi/).

Most governments, including the centre, therefore plead helplessness, even innocence, given this historical baggage.

Specious tales

But that is not entirely true. Charitable and religious institutions are under the Concurrent List of the Constitution as Item 28 in List 3 of Schedule 7 under Article 246 (2). Therefore, it is possible for the Parliament to legislate for releasing the Devaswom administration from the hold of the State Government and ruling political party.

Moreover, there is Article 26 of the Indian Constitution which gives every religious group a right to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes, manage its affairs, properties as per the law, “Freedom to manage religious affairs. Subject to public order, morality and health, every religious denomination or any section thereof shall have the right … to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes; … to manage its own affairs in matters of religion; to own and acquire movable and immovable property; . . . and to administer such property in accordance with law.”

It was these laws that Swami Kesavananda Bharati, who passed away on 6 September 2020, sought shelter under. He challenged the state government of Kerala from taking control of the lands of the Sri Edneer Mutt from which it earned its livelihood. Accidentally, he became “the sole unwitting petitioner in the historic Fundamental Rights case”, which prevented the nation from slipping into a totalitarian regime (https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/kesavananda-bharati-swamiji-of-edneer-mutt-passes-away-at-80/article32534308.ece).

Kesavananda Bharati, then a young man in his 20s, and the hereditary head of a mutt in Kerala, had little idea that the case he filed would end up being such a landmark. He took umbrage at the Kerala government’s attempt to impose restrictions on the management of religious property through land reform legislation, Bharati filed the suit questioning its constitutional propriety. The case came to the attention of Nani Palkhivala, who recognised its possibilities, particularly the prospect of challenging three Amendments — the 24th, 25th and 26th — to the Constitution. The case had now evolved into a dispute over Parliament’s power under Article 368 to amend the Indian Constitution.

Unfortunately, the mutt eventually lost its properties since the laws challenged by it were upheld, even though the “basic structure” doctrine – which prevented Parliament from changing the basic structure of the constitution – was upheld. As a result, the mutt lost its source of income and had to depend on donations (https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/kesavananda-bharati-seer-behind-basic-structure-of-constitution-case-dies-aged-79-at-his-kerala-ashram/story-epboHW2HkeboWAg7Y9XmCP.html).

In the meantime, several other rich temple trusts were taken over the governments of various states. These included Tirupati, Meenakshi, Shirdi and Siddhi Vinayak.

The challenge begins

Governments controlling temple trusts and temple lands remained unchallenged till recently. That was when the state of Tamil Nadu tried to take over the  Chidambaram temple trust. But then came a challenge from an unanticipated quarter.

Chidambaram temple trust. But then came a challenge from an unanticipated quarter.

The temple trustees challenged this move. The battle finally ended with a Supreme Court verdict on January 6, 2014. Through a two-member bench the apex court ordered the Tamil Nadu government to desist from any attempt to take over the Chidambaram Trusts (http://judis.nic.in/supremecourt/imgs1.aspx?filename=41133) .

It stated, “Even if the management of a temple is taken over to remedy the evil, the management must be handed over to the person concerned immediately after the evil stands remedied. Continuation thereafter would [be] tantamount to usurpation of their proprietary rights or violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution in favour of the persons deprived. Therefore, taking over of the management in such circumstances must be for a limited period… Supersession of rights of administration cannot be of a permanent enduring nature.”

The Supreme Court also told the government that it had no business managing the affairs of temples (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/09/entrepreneur-godmen-flourish-as-hindu-temple-trusts-nationalised/)

It was hoped that other temple trusts would also seek protection under the umbrella of this verdict. But since trustees of most big temples are government appointed, none has dared become independent of the government.

Money and power

As TR Ramesh, a banking professional and a research scholar of law relating to Hindu Religious Institutions and President of the Temple Worshippers Society in Chennai, points out (see box item), the Tamil Nadu  government alone has caused losses of at least Rs.6,000 crore each year to the temples in that state (http://www.esamskriti.com/e/National-Affairs/For-The-Followers-Of-Dharma/Supreme-Court-Judgment-In-Chidambaram-Temple-Case-~-What-Next-1.aspx).

government alone has caused losses of at least Rs.6,000 crore each year to the temples in that state (http://www.esamskriti.com/e/National-Affairs/For-The-Followers-Of-Dharma/Supreme-Court-Judgment-In-Chidambaram-Temple-Case-~-What-Next-1.aspx).

Temples begin to fight back

It was possibly the verdict in the Chidambaram temple matter. Or it could be the Supreme Court’s own realisation that all was not well with governments trying to own, manage and even misuse temple trusts. The fact is that the government is being increasingly challenged in the courts.

Take the case of Vaishno Devi. In April 2020, a challenge was made to the Constitutional validity of the Jammu & Kashmir Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board Act, 1988, which vests control over the shrine in the hands of the government (https://www.barandbench.com/news/litigation/vaishno-devi-shrine-board-funds-were-used-for-iftaar-parties). Allegations include that corruption is now apparent in the working of the government-controlled shrine board. The pliant says that government officials nominated on the temple board had squandered the shrine board funds for throwing Iftaar parties. Further, the board had begun employing several non-Hindus at various posts in its administration.

In July 2020, the Supreme Court (SC) ruled against the takeover of Thiruvananthapuram’s historic Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple by the government. The apex court upheld the right of the Travancore Royal family in the administration of the temple (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/supreme-court-sets-aside-kerala-hc-order-on-government-takeover-of-padmanabhaswamy-temple-5540371.html).

In Uttarakhand (a BJP ruled state), devotees including Member of Parliament Subramaniam Swamy objected to the government takeover of 51 temple trusts (including Kedarnath and Badrinath) in that state (https://www.pgurus.com/uttarakhands-51-temple-takeover-case-bjp-govt-objects-to-subramanian-swamys-petition/). The state government justified this takeover in the High Court and expressed displeasure at Swamy’s tweets against the takeover of the temple. Asking for rejection of Subramanian Swamy’s petition, the BJP-ruled Uttarakhand Government claimed that the takeover of the temple was necessary due to natural calamities and to have transparent conduct of Char Dham pilgrimage in future. Specious arguments in the greed for money and power. The matter is being heard by the courts.

In May 2020, there was a renewed challenge to the government’s takeover of the Guruvayur temple trust, as the opposition BJP party questioned the Pinarayi Vijayan-led Kerala government for making Guruvayur Devaswom Board transfer Rs 5 crore from its fixed deposit to the Chief Minister’s relief fund (https://www.organiser.org/Encyc/2020/6/12/Hindu-Temple-money-for-Secular-Kerala-government-Swami-Chidananda-Puri.html).

In January 2020, Shirdi residents called for an indefinite shutdown after a prominent politician called Pathri in Parbhani as the birthplace of the 19th-century saint Sai Baba and said he will allot Rs 100 crore for its development (https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/shirdi-to-shutdown-over-cm-uddhav-thackeray-s-remark-on-sai-baba-s-birthplace/story-mD2EkSKlO8A393KqDd9tKM.html). But a formal challenge of the temple shrine’s takeover hasn’t begun as yet, though the rumblings of dissent are mounting.

In August 2020, the Bombay High Court issued notices to Maharashtra government and Siddhivinayak Temple Trust seeking their responses to a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) challenging the transfer of Rs 10 crore to the government.

In 2018, Subramaniam Swami, who was one of the key petitioners in the Chidambaram case, argued for reversing the takeover of the Tirupati Tirumala temple trusts (https://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/bjp-mp-subramanian-swamy-seeks-tirupati-temple-to-be-taken-out-of-government-control-supreme-court-asks-him-to-move-andhra-high-court/1316642/). In September the same year, a bench of Justices R F Nariman and Indu Malhotra of the Supreme Court asked Swamy to move the Andhra Pradesh High Court with his plea challenging the provisions of a state law by which the administration and control of Hindu religious institutions were taken over by the state government.

In 2018, Subramaniam Swami, who was one of the key petitioners in the Chidambaram case, argued for reversing the takeover of the Tirupati Tirumala temple trusts (https://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/bjp-mp-subramanian-swamy-seeks-tirupati-temple-to-be-taken-out-of-government-control-supreme-court-asks-him-to-move-andhra-high-court/1316642/). In September the same year, a bench of Justices R F Nariman and Indu Malhotra of the Supreme Court asked Swamy to move the Andhra Pradesh High Court with his plea challenging the provisions of a state law by which the administration and control of Hindu religious institutions were taken over by the state government.

Clearly, the Hindus are gradually waking up to fight the government’s encroachment on their temple funds, even culture. The sheer irony is not lost on many temple priests and Hindu community leaders. At one time, they had to fight Aurangzeb. This time, they must fight (both state and central) Indian governments as well.

COMMENTS