https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/lessons-to-be-learnt-about-npa-recovery/1428359

NPA recovery is not easy to manage

RN Bhaskar January 3, 2019

The recently published Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India 2017-18 brought out by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is a veritable goldmine of information on banking and non-performing assets (NPAs) in India (https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/AnnualPublications.aspx?head=Trend%20and%20Progress%20of%20Banking%20in%20India).

Read between the lines, and you get a fair idea of what has gone wrong with banking in this country.

Read between the lines, and you get a fair idea of what has gone wrong with banking in this country.

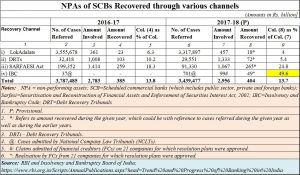

Take for instance the table given alongside.

It will tell you of how different types of debt recovery systems functioned in India. Watch the numbers in column 9. The figures in these columns will tell you how efficient NPA resolutions systems have been. It will tell you that the least efficient was the Lok Adalat route to NPA resolution. Then, in the pecking order, came the debt recovery tribunals (DRTs), followed by proceedings under the SARFESI Act, and finally the IBC or the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code.

IBC managed to recover almost Rs.49 billion of the Rs.99 billion that was involved. That gives this method a recovery rate of 49.6%.

But there are good reasons to hold the applause for a while. Study the numbers in column 6. They give you the number of cases that were referred to each type of NPA resolution mechanism. Thus the Lok Adalat was burdened with 3,317,897 cases during 2017-18. As many as 29,551 cases were referred to the DRTs. SARFESO accounted for 91,330 cases. Interestingly, only 71 cases were admitted by National Company Law Tribunals (NCLTs) under the IBC.

By focussing on fewer cases involving very large sums of money, the NPA resolution system under the NCLT could cope more effectively with resolving the issue of bad debts than other mechanisms could. When you burden a system with too many cases and don’t even bother to increase the number of people who can deal with such cases, you actually create a situation where justice will not be delivered, and the malaise is allowed to fester. If more NCLTs (and more people) are not put into place as the number of cases mount, expect the IBC also to end up like the Lok Adalat, DRT and Sarfesi

Part of India’s problem of bad debts is the ever present hand of the politician-bureaucrat combine to grant loans to the undeserving, by breathing heavily down the necks of bankers. Then they ensure that the debt recovery mechanisms are burdened with too many cases. This is further compounded by allowing very few people to adjudicate matters, so that the pile-up of cases ensured little resolution. This has been done with the courts till now. Debt recovery mechanisms are neutralised using the same strategy (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/09/3-measures-can-stop-india-becoming-failed-state/)

All along India has specialised to creating systems designed to defraud, then structured to ensure that the guilty do not get penalised (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/08/banker-scams-ter-and-visible-hand-make-merry/).

That could explain the terrible state of public sector banks (PSBs) compared to private and foreign banks. The RBI reports tells you how, in 2017-18, public sector banks accounted for NPAs worth almost Rs.9 lakh crore (Rs.9 trillion). In sharp contrast, private banks accounted for just 1.3 trillion of NPAs while foreign banks accounted for barely Rs.138 billion. The buck stops at the doorstep of the largest shareholder of the worst performers (the PSBs) which happens to be the government. It just did not (want to) set things right.

As a result, in 2017-18, you have PSBs accounting for 14.6% of gross NPAs, while private banks registered 4.7% and foreign banks 3.8%. Collectively, all scheduled commercial banks accounted for gross NPAs of 11.2%.

Current capital adequacy norms require banks to have at least one-tenth of their advances as owned funds (share capital plus reserves). With gross NPAs hovering at 11.2%, it is quite clear that the banking sector has eroded its own capital. And with the government proposal in Parliament for enhancing bank recapitalisation outlay from Rs 65,000 crore to Rs 1,06,000 crore (or Rs.1.06 trillion) it is obvious that the Indian banking sector will continue to limp.

Add to this the flight of investment funds away from India, the worsening borrowing climate thanks to the clamour for loan writeoffs, and the global economic slowdown that is likely to maul all countries in the world, expect the banking sector to continue hobbling along during 2018-19.

The government’s unwillingness to ask the election commission to ban the announcement of loan waivers is worrisome. It means that the door for offering loan waivers has been kept open.

That does not augur well — either for the farmers whose loans are sought to be written off, or even the banking sector.

The pains in the financial sector are far from over.

COMMENTS