https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/opinion-farmers-in-india-dont-earn-much-many-are-terribly-exploited-2892291.html

Farmers earn little; they remain exploited – Nabard

The current model adopted by the government — of being both the subsidy provider and the procurement price player — has failed to deliver good results. It has made the farmer lose incomes and even self-respect

RN Bhaskar — Aug 30, 2018

If farmers have been on the warpath in many states across the country, they have good reason for their anger. Two reports, one by Nabard (https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/tender/1608180417NABARD-Repo-16_Web_P.pdf) and the other by India Ratings (https://www.indiaratings.co.in/PressRelease?pressReleaseID=33569&title=Rural-Wage-Growth-No-Less-Important-than-Doubling-Farmers%E2%80%99-Income) tell a story that is different from what state and central governments like to tell.

Take a look at table 1. Rural incomes have been pathetic in most states, including Maharashtra which boasts of doing so much for farmers.

Take a look at table 1. Rural incomes have been pathetic in most states, including Maharashtra which boasts of doing so much for farmers.

The states where farm prosperity is high have not seen farmer agitations. Hence, one does not hear about farmer agitations in the Punjab, Kerala, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Goa. They have erupted in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, because the farmer does not earn enough. While Madhya Pradesh has climbed from being a Bimaru state to one which has made farmers a lot more prosperous than in the past (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/comment-what-makes-madhya-pradesh-tick-2583155.htmlMoneycontrol), Maharashtra has done precious little. Instead of protecting the entire farm sector, it has focussed on the welfare of farmers who are close to cooperatives – mostly run by the Congress and the NCP. Hence only 20% of the land is cultivated in Maharashtra compared to 67% in Madhya Pradesh. Clearly, water has been cornered by the sugarcane and cotton lobbies. Not surprisingly, farmer distress is greater in this state.

True, Gujarat’s farmers earn more than their counterparts is most states. That is proof that the farmer agitation there is more political than based on poor remuneration for farmers. The agitation there needs a political, not a commercial, solution.

But the agricultural story looks a lot worse when as one studies the Nabard report further. It points to a bigger farm crisis than had been imagined earlier.

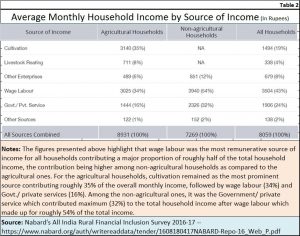

Just take a look at the figures alongside (table 2). They suggest that the average income from cultivation was just Rs.3,140 per household per month. This is pathetically low. Worse are incomes from livestock rearing which generated only Rs.711 a month. If state governments had put in place the right systems, this number for income from livestock could have been closer to Rs.3,000 per cattle per month.

Just take a look at the figures alongside (table 2). They suggest that the average income from cultivation was just Rs.3,140 per household per month. This is pathetically low. Worse are incomes from livestock rearing which generated only Rs.711 a month. If state governments had put in place the right systems, this number for income from livestock could have been closer to Rs.3,000 per cattle per month.

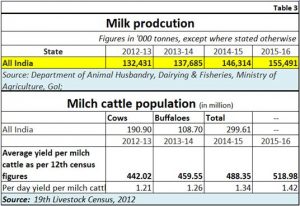

The poor income from animal husbandry is on account of two factors. Average yield per cattle is just around 1.4 litres per day (see table3). It should have been 3 at the minimum and 10 on the average. Compounding this is the ill-advised ban on cattle slaughter. It deprives cattle-owners from earning around Rs.20,000 from the sale of each cattle-head when it becomes old. That means a loss of another Rs.1,500 a month.

The poor income from animal husbandry is on account of two factors. Average yield per cattle is just around 1.4 litres per day (see table3). It should have been 3 at the minimum and 10 on the average. Compounding this is the ill-advised ban on cattle slaughter. It deprives cattle-owners from earning around Rs.20,000 from the sale of each cattle-head when it becomes old. That means a loss of another Rs.1,500 a month.

Cattle yields ought to be around 3-7 litres a day. State governments – over the past seven decades — have failed to educate farmers into using good artificial insemination sperm.

Cattle yields ought to be around 3-7 litres a day. State governments – over the past seven decades — have failed to educate farmers into using good artificial insemination sperm.

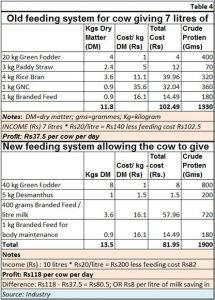

Moreover, as industry experts point out, just a change in feed allows a yield of 7 litres to swell to 10 litres. That pushes up farmer profits (not turnover) from Rs.40 to Rs.100 per cattle per day (see table 4). That can make a farmer earn Rs.3,000 per cattle per month.

This is gross negligence on the part of animal husbandry staff in most states. They have failed to teach farmers how to augment their income. States like Maharashtra have the dubious distinction of letting farmers get Rs.25 a litre but by making the state bail out the cooperatives. Instead of making the cooperatives pay Rs.25 a litre, the state has allowed them to pay Rs.20, and has agreed to pay a subsidy of Rs.5 per litre to farmers. In doing so, it has burdened taxpayers with Rs.3,000 crore a year. When Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu pay over Rs.26 and some over Rs.36 a litre, why can’t Maharashtra’s. The state government has been more fair to cooperatives than to its tax paying citizens.

The Nabard data shows that farm distress is even more severe than revealed by the table on averages. The amounts earned by marginal farmers is painfully pathetic. As the Nabard report states, almost 20% of households “earned ₹ 2,500 or lesser per month which appears insufficient to meet the bare necessities of life.” At the same time, adds the report, “A sharp rise was seen in the households falling in the top 20th percentile, with income level rising from roughly ₹ 11,000 to ₹ 48,833 per month. The rise in income was much steep in the 99th percentile households which earned more than twice the ones in the 95th percentile and about four times the ones in the 80th percentile.” In other words, rich farmers got richer. Poor farmers remained where they were, or even got poorer.

These figures, states the Nabard report, “are reflective of wide income disparities in the rural communities with a very large divide between the rich and the poor. These disparities may be attributed to existing inequalities in terms of households’ ability to access various resources and opportunities which are essential for their development.”

The story of inequity is the same as for the rest of the Indian economy. The top 20% of people account for over 90% of the wealth in the country. The bottom 20% barely manages to survive.

But it should have been different for agriculture and rural communities. After all, so much is spent by the government on subsidies and doles, year after year. It should certainly have been different for milk producers where a working model exists in Gujarat – thanks to Dr. Verghese Kurien — and where farmers get over Rs.30 per litre without state subsidies.

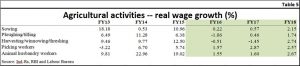

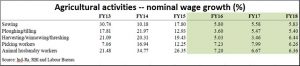

The Nabard findings are reinforced by data from India Ratings. In its report of 23 August, 2018, (https://www.indiaratings.co.in/PressRelease?pressReleaseID=33569&title=Rural-Wage-Growth-No-Less-Important-than-Doubling-Farmers%E2%80%99-Income),

The Nabard findings are reinforced by data from India Ratings. In its report of 23 August, 2018, (https://www.indiaratings.co.in/PressRelease?pressReleaseID=33569&title=Rural-Wage-Growth-No-Less-Important-than-Doubling-Farmers%E2%80%99-Income),  IndiaRatings shows how farmer incomes have stopped growing significantly during the past three years (see rtable 5).

IndiaRatings shows how farmer incomes have stopped growing significantly during the past three years (see rtable 5).

That is when the penny drops. Doubling of farm incomes is obviously not the solution. Doubling Rs.2,500 a month will fetch the farmer only Rs.5,000. That is still distressful. The best way of ensuring a better deal for the farmer is by guaranteeing him a fair percentage of the market price of what he produces. A 50% share of the market price ought to be the norm. It would be a bit lower than the share of 80% of the market prices that Gujarat’s milk cooperatives offer their farmers (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/opinion-for-farmers-to-make-money-the-government-should-move-out-of-procurement-2830791.html). Anecdotal evidence shows that farmers often get as little as 10% of the market price. That is where the root cause of farm distress lies.

Maybe the current model adopted by the government — of being both the subsidy provider and the procurement price player — has failed to deliver good results. It has made the farmer lose incomes and even self respect. Could India allow instead a bigger role for market forces, and a system linked to consumer prices? Could the farmers finally get a better deal?

COMMENTS