http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/comment-from-jobless-growth-to-wary-foreign-investors-the-dark-clouds-on-the-indian-economy-are-here-to-stay-2515845.html

The Indian economy and the continuing slowdown

There are three reasons to doubt the government’s belief that economic growth will rebound sharply.

RN Bhaskar – Feb 25, 2018 07:24 PM IST

The tea leaves predict more pain in the coming months for the Indian economy. This is notwithstanding the encouraging remarks made by the Economic Survey 2018 that it expects “real GDP growth to reach 6.75 percent for the year as a whole, rising to 7-7.5 percent in 2018-19, thereby reinstating India as the world’s fastest growing major economy.”

There are three reasons for this author to take the claims of the Economic Survey with a pinch of salt.

First, yes, GDP will grow, but not because of actual economic growth. You can have jobless economic growth as well, as has been witnessed during the last few years of the previous government. If you have growth without job formation – so very critical in a populous country like India – that growth remains unsustainable. There are good reasons to believe that some of the economic growth witnessed in the data provided to the country could have been because of epayments (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/beware-the-merchant-charge-that-could-boost-gdp-spur-inflation-2459237.html).

Epayments alone have the potential of pushing up economic growth by around 2 percentage points per annum over the next 4-5 years. But its contribution is concealed in the figure for services. Given the nascent form of this industry, it would be safe to assume that 1-2% of GDP growth came from merchant discounts paid on the value of the transactions. It might be worth remembering that even when one considers the (now extant) Rs,1,000 note, cash was always a cheaper option than epayments. The cost of printing a Rs.1,000 note was Rs.34. The currency note was good enough to last out some three years (let us assume 1,000 days). According to date provided by the RBI, the note used to have a velocity of one transaction a day on an average. Thus over 1,000 days, the total cost of transacting through cash was only Rs.34 – which is the cost of printing the note.

When you consider epayment, every transaction of Rs.1,000 could result in merchant discounts (MDR) of around Rs.10. Thus over a period of 1,000 days, the total MDR payout is Rs.10,000. Now compare the Rs.34 with Rs.10,000 and you will realise why GDP can swell with the introduction of epayment.

There is a possibility that India’s GDP will continue to grow because of this MDR for the next few years. But it won’t create jobs unless the country focuses on forensics and systems audits as well.

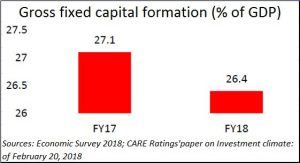

Second, economic growth takes place when there is some investment for embarking on a new type of (or enhanced) economic activity. This is known as gross capital formation. India’s GCF has been declining as a percentage of GDP (see chart). This does not augur well for healthy economic growth. In fact, this and a set of other figures has been brought out quite succinctly in a recent paper (20 February, 2018) by CARE Ratings.

Second, economic growth takes place when there is some investment for embarking on a new type of (or enhanced) economic activity. This is known as gross capital formation. India’s GCF has been declining as a percentage of GDP (see chart). This does not augur well for healthy economic growth. In fact, this and a set of other figures has been brought out quite succinctly in a recent paper (20 February, 2018) by CARE Ratings.

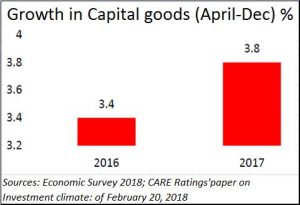

The only bright spot in the picture appears to be growth in capital goods. But even here the picture is a bit mixed. This growth came because of non-electrical machinery, computers and electronics. The big worrisome decline was in electrical machinery. This does cause anxiety because electrical machinery is what makes factories hum. A 15% decline on this front is naturally a bit disconcerting.

The only bright spot in the picture appears to be growth in capital goods. But even here the picture is a bit mixed. This growth came because of non-electrical machinery, computers and electronics. The big worrisome decline was in electrical machinery. This does cause anxiety because electrical machinery is what makes factories hum. A 15% decline on this front is naturally a bit disconcerting.

The most threatening of clouds appear to be those relating to new investments and new projects. This is where one suspects that cause is the slowing down on fresh foreign investments. Much of foreign investment had begun to dry up because of the reluctance on the part of the Indian government to allow any investor to opt for

The most threatening of clouds appear to be those relating to new investments and new projects. This is where one suspects that cause is the slowing down on fresh foreign investments. Much of foreign investment had begun to dry up because of the reluctance on the part of the Indian government to allow any investor to opt for  international arbitration in a seat outside of India. The government wants such litigants to approach other centres of arbitration – outside of India – only after exhausting all available courses of legal redress within India first. As pointed out in these columns (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-asking-for-investments-is-good-but-can-india-guarantee-speedy-and-fair-grievance-redressal-2489553.html), such a move has had the unfortunate, but expected, reaction of slowing down foreign direct investment into India. The last thing any foreign investor wants is to get bogged down by the cumbersome processes of India’s law enforcement and judicial processes. This is where reform is urgently needed. Since that is not possible, investors prefer to take recourse to a speedier judicial resolution in centres outside of India – as allowed by the Geneva convention to which India is a signatory.

international arbitration in a seat outside of India. The government wants such litigants to approach other centres of arbitration – outside of India – only after exhausting all available courses of legal redress within India first. As pointed out in these columns (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-asking-for-investments-is-good-but-can-india-guarantee-speedy-and-fair-grievance-redressal-2489553.html), such a move has had the unfortunate, but expected, reaction of slowing down foreign direct investment into India. The last thing any foreign investor wants is to get bogged down by the cumbersome processes of India’s law enforcement and judicial processes. This is where reform is urgently needed. Since that is not possible, investors prefer to take recourse to a speedier judicial resolution in centres outside of India – as allowed by the Geneva convention to which India is a signatory.

India is believed to have allowed this benefit to Japan in the recently concluded CEPA (Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement) between the two countries where India is believed to have allowed Japan’s investment managers to opt for international arbitration in seats outside this country (neither the Japanese nor Indian bureaucrats are willing to confirm or deny this). But hardly had the ink dried on this agreement that the government slapped a taxation charge against Nissan. When the Japanese company tried to approach an overseas centre for arbitration, it was dragged to Indian courts challenging such a move. The matter remains in the courts at the moment.

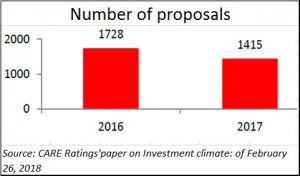

Not surprisingly, the numbers relating to investments and proposals have been terrible. The number of proposals declined from 1,728 in 2016 to 1415 in 2017. This number could continue to fall, unless remedial steps are taken.

Not surprisingly, the numbers relating to investments and proposals have been terrible. The number of proposals declined from 1,728 in 2016 to 1415 in 2017. This number could continue to fall, unless remedial steps are taken.

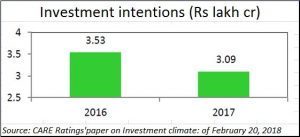

Even the intent to investment numbers registered a decline from Rs.3.53 lakh crore (or Rs.3.53 trillion) to Rs.3.09 lakh crore in 2017.

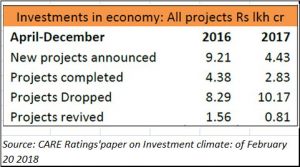

Naturally, this was bound to have resulted in actual investment in India (see chart). During the April-December period, total investments in new projects almost halved from Rs.9.21 lakh crore in 2016 to Rs.4.43 lakh crore in 2017. Projects completed also reduced by a third (see chart). The number of projects dropped swelled, while the number of projects revived held out no cheer at all.

There is a possibility that foreign investments in the biggest job producing areas will continue to shrivel, till the government agrees to allow investors the right to approach other judicial redressal centres. At the same time, the government should work hard to ensure that credibility in India’s redressal systems goes up. This is going to be extremely difficult if the government goes slow on the appointment of judges (in spite of the existing numbers being short of the sanctioned vacancies).

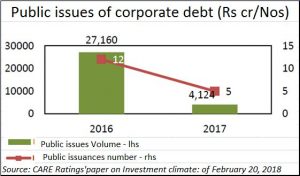

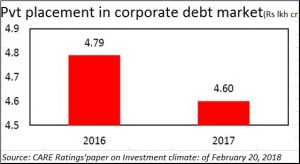

The mood in the markets has become so bad that private placement in the corporate debt market has shrunk. Good companies did resort to debt markets because they could get better rates from investors than from banks. The banks, saddled with the leftovers, were a bit shy. However, what is alarming is that these ‘leftovers’ could not raise money from debt markets either. The

The mood in the markets has become so bad that private placement in the corporate debt market has shrunk. Good companies did resort to debt markets because they could get better rates from investors than from banks. The banks, saddled with the leftovers, were a bit shy. However, what is alarming is that these ‘leftovers’ could not raise money from debt markets either. The  confidence that promoters showed in the past appears to have been shaken. And the manner in which government and the law enforcement authorities have gone about handling the Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi cases leaves much to be desired.

confidence that promoters showed in the past appears to have been shaken. And the manner in which government and the law enforcement authorities have gone about handling the Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi cases leaves much to be desired.

Compare the manner in which Indian banks recover money from the approaches made by Standard Chartered Bank (Stanchart) in recovering the money owed to them by the Ruias of Essar. The amount owned to Stanchart was at least five times the amount allegedly embezzled by Nirav Modi. But there was no public outcry, no public shaming and naming, no move to involve either the police or the enforcement directorate. Stanchart is believed to have got Rosneft to acquire some of Essar’s assets and thus got its money back.

In fact, watching Stanchart’s moves, ICICI Bank and YES Bank threatened to file cases in the US for attachment of Essar assets, and both managed to recover some of the money that the Ruias owned them. Indian government-owned banks and the law enforcement authorities have still not learnt the way to recover money without killing a corporate brand or a business activity. The government did this when it banned commodity markets to punish NSEL. It has done the same again this time as well. The only time the government protected a business was in the Satyam case. In most other cases, it has allowed the business to die, and often allowed the errant promoter to flee the shores of India. (see article on why did the dogs not bark at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/02/pnb-why-did-the-dogs-not-bark/).

Thus the country is confronted with a depressed market sentiment. People who want in invest in India have deferred their plans till they see improvements on three fronts.

They want to see an improvement in judicial redressal systems. In fact, it is surprising to see constitutional posts like Supreme Court judges and the chief Justice of India not being guaranteed a minimum tenure of five years, as is the case with other constitutional posts.

Till such systems are put into place, and till they have confidence in such systems, foreign investors want recourse of international arbitration in a seat outside of India. It is no use having the government declare that it has an arbitration centre in Mumbai, or that it will ensure speedy trials. It is for the investors to say that judicial processes are fair and effective.

Finally, most investors are also alarmed by the selective approach towards enforcement activities. Consider how the police swooped down on the Delhi CM’s residence in the case of a senior bureaucrat being slapped. Now compare this with the muted response of the government and the law enforcement machinery when another elected representative beat up a public servant 12 times and broke his spectacles. Even the courts did not take suo moto cognizance of the way rights and civil liberties were trampled upon. How does one explain the difference in tackling such effrontery on the part of elected representatives? It is this inability to check such brazenness that also worries investors.

The government appears to have forgotten that money is always skittish. It disappears at the first sign of trouble. Then, if it does choose to return, it will ensure that the risk-related charges will be high and that too after third party guarantees are put into place.

India is rapidly hurtling towards such a situation. The willingness to name and shame rather than resolve is a big problem. Consider how BOC Aviation, a Singapore company could – without too much of fanfare — get damages of US$ 9 million from Vijay Mallya. Yet the Indian government could not. Its inability to guarantee protection of rights and privacy is another factor that worries global players. Its penchant for naming and shaming horrifies investors. They know how much work is involved in building a brand, and how easily it can be damaged because of reckless government action – it is worth recalling the nightmarish moments Nestle had to go through in its battle against the food control authorities (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2015/10/food-drugs-ban-leads-to-caprice-and-corruption/).

Will India learn to get back to basics and practice responsible judicial and law enforcement processes? Your guess is as good as mine.

COMMENTS