http://www.freepressjournal.in/business/budget-2018-the-spirit-is-quite-willing-but-the-flesh-is-terribly-weak/1214090

Budget 2018 is high on intent, but weak on the underpinnings

— By | Feb 02, 2018 11:27 am

As Budgets go, this budget could mark a watershed. It has all the ingredients India needs. It talks about ways to reduce the time taken for litigation, it seems to address the issue of farmer distress; and it has a genuine concern for improving healthcare. Together they could mark a transformation of the entire country.

The most important focus point of the budget is agriculture. It enjoys the largest outlay. The finance minister outlined a slew of measures to boost agricultural production and the rural economy. He announced new projects as well as enhanced support for existing schemes. The cumulative outlay for all of them comes to around Rs 14.34 lakh crore (trillion).

There can be no denying that the need to ameliorate agriculture is crucially important. First, because 50 per cent of India’s population is engaged in agriculture and related activities account for only around 14 per cent of its GDP. The mismatch is jarring. Something must be done to increase the value of agricultural output. One way is by increasing prices. Another way is by improving value added. To give agriculture its rightful place, both are needed.

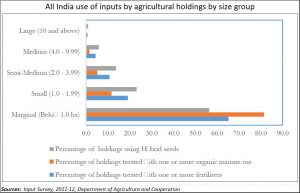

Contrary to public opinion, increase in farm prices need not be inflationary. This is because almost 200-400 per cent of the farm price is taken away by the middleman and the trade. If the farmer could have a decent price, and had cost-effective access to markets, both the farmer and the consumer would benefit. The reality is that the small farmer suffers the most (see chart). Hence the government’s decision to give farmers 1.5 time the cost of production is most welcome. But there are some problems.

First, it is confined to the kharif crop. Rabi crop growers are exempted. Second it covers only cereals coarse grains and some pulses. Horticulture is left out. Third, it does not take into account that to procure bajra, jowar and pulses, the country needs more warehouses (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/08/is-wdra-a-functioning-organisation/). The current warehousing capacity – even for wheat and rice – is inadequate. Procuring more, could then mean more grains rotting.

First, it is confined to the kharif crop. Rabi crop growers are exempted. Second it covers only cereals coarse grains and some pulses. Horticulture is left out. Third, it does not take into account that to procure bajra, jowar and pulses, the country needs more warehouses (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/08/is-wdra-a-functioning-organisation/). The current warehousing capacity – even for wheat and rice – is inadequate. Procuring more, could then mean more grains rotting.

The way out of procurement is by converting all FCI and State Warehousing Corporation (SWC) godowns into commodity exchange managed godowns. These need qualified auditors and assayers. Only then will the dematerialised receipts work. And to get money from banks against dematerialised receipts, you need to allow price discovery for spot and futures markets through commodity exchanges. That means the government should not ban trades in commodities or even close down commodity exchanges that it has been doing till now. Without all this, it is possible that the farmers will get 1.5 times the price of produce. But the grains will be left to rot.

Then take healthcare. The government wants the new medicare provisions to cover as many as 10 crore families. It wants each family covered under the new National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS). This would allow them to get medical reimbursement for treatment at hospitals up to a maximum of Rs 5 lakh every year. The flagship health care scheme could become the world’s largest government-funded health programme — Ayushman Bharat Programme.

But where are the doctors. The government wanted to meet this problem by allowing homeopaths and ayurveds to become allopaths by appearing for a bridge examination (the matter is now before the Supreme Court). If a bridge course could be the answer, why not have bridge courses for clerks to become judges, or to become IAS officers?

The solution could lie in two measures. First, increase the number of medical colleges, thus ending the licence raj for medical college permissions. To ensure quality education is provided, the government could have exit exams each year – along the lines of the JEE for engineering. Medical colleges with poor results would lose both the colleges and management control of the institutions, which could then be transferred to good managements.

For the short term, make rural practice in primary health centres (PHCs) compulsory for all medical students each year for six weeks. That way, reasonably competent people get to man the PHCs and the government’s rural programmes can work. The answer is not to degrade the quality of education itself. But the budget is silent about this.

On the judicial redressal front too, the problem will be the shortage of judges. Even existing vacancies have not been filled. And India needs at least twice the number of sanctioned judges at the high court levels to clear the backlog caused at lower courts. Only then will judicial delays get remedied. Instead, the government has moved to prevent companies even going to other countries for international arbitration (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/01/asking-investments-good-can-india-guarantee-speedy-fair-grievance-redressal/). That is quite unfortunate.

To conclude, the budget has the best of plans and intentions. But unless the underlying processes and issues are addressed first, many of these plans may not be implementable.

COMMENTS