http://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/economic-growth-continues-to-falter/1202361

Economic growth sputters. . .

— By | Jan 11, 2018 07:30 am

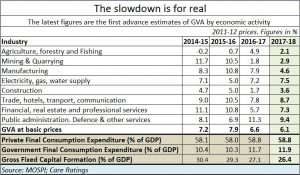

So it is finally official. For the second year in a row, India’s GVA (Gross Value Added) growth has slowed down. It went up during 2015-16. It appeared that the Modi magic was beginning to work. But the subsequent years have been a dampener.

What should worry politicians most is the drop in the growth rates of agriculture. Agricultural growth rates were promising immediately after the Narendra Modi government was formed. It climbed from -0.2% in 2014-15, to 0.7% in 2015-16. This was confirmed by a further increase in the growth rate to 4.9% in 2016-17. But in 2017-18 it had slipped back to 2.1%. Something had gone wrong.

What should worry politicians most is the drop in the growth rates of agriculture. Agricultural growth rates were promising immediately after the Narendra Modi government was formed. It climbed from -0.2% in 2014-15, to 0.7% in 2015-16. This was confirmed by a further increase in the growth rate to 4.9% in 2016-17. But in 2017-18 it had slipped back to 2.1%. Something had gone wrong.

For the Modi government, agricultural growth is crucially important. The government wanted to usher in at least half the growth rates (of 10%) achieved in Gujarat when Modi was chief minister there. It is a very important vote bank that the BJP wanted to nurture and exploit. The government has also promised to double farm incomes by 2022. A slowdown in this sector sends up warning smoke signals. What happened?

There could be three possible reasons.

First, it must be noted that agriculture and the rural sectors are essentially cash based economies. Consequentially when 86% of total currency is sucked out of the system through the ban on Rs.500 and Rs.1000 currency notes, the rural sector was bound to be hit.

The other reason could be the pain that farmers suffered when the ban on cow slaughter was announced. What worsened it was the ban on transportation of buffaloes as well. The ban on cow slaughter had already made many farmers switch to buffaloes (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/03/cow-belt-makes-cows-an-endangered-species/). But when screaming vigilantes made all beef suspect, and when the government further introduced a ban on transporting buffaloes as well, the farmers were grievously hurt.

This is simply because the man who pays for a cow or buffalo expects to make money out of this investment. Therefore, when the cow or buffalo stops yielding income – especially when age curtails its ability to procreate, hence lactate – the farmer has to sell the animal. The farmer normally gets Rs.20,000 for an old cow or buffalo. He uses this to subsidise the cost of purchasing a young animal which has a market price of around Rs.50,000-60,000.

When he is unable to get the Rs.20,000 from the sale of an aged animal, he postpones the purchase of the new young animal too. He knows that in addition to getting no income, he will have to spend more on food and medicine to take care of the old animal. To cope with this crisis, he postpones all purchase decisions. Could that have caused a slowdown in the agricultural sector?

Third, the entire cattle economy affected other sectors as well – beef and leather. The cattle farming economy was largely restricted to self employment through backyard rearing of less than 10 cattleheads per household. But the other sectors were very large employment and revenue generators. Both beef and leather were among the largest exporting industries too.

Beef, for instance, had already pushed India to becoming the third largest exporter of this meat in the world. ADB data (http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7465e.pdf) makes special reference to India’s position in the global market for beef and veal. India ranked next to Brazil and Australia. Uttar Pradesh alone accounted for annual beef exports of over Rs.11,000 crore. Suddenly this industry was threatened. At stake were exports and jobs.

Leather too was both a big employer and a big exporting industry. But unlike beef, it had a large domestic market as well. The people employed here could run into millions. The total losses to this industry cannot be estimated easily because even animals which die a natural death can be skinned for leather, though this leather is inferior to the one take from healthier animals.

When two key segments of employment are under attack, it is inevitable that lost jobs would mean lower consumption budgets. That could trigger a slowdown in other sectors as well.

But there is a possibility that this slowdown will wake up the government to announce amends. There are two other pressures working against the government where the cattle ban is concerned. One is the Supreme Court’s ire against the gau rakshaks (cow protection vigilantes) and the ban on transportation of buffaloes. The government has expressed its willingness to modify the laws.

Another pressure point is political. Most of the people employed by the beef and leather industries are either Dalits or Muslims. The government is now wary of these groups coming together to express their unhappiness about this ban. The recent demonstration of rising political awareness of the Dalits in Gujarat and Maharashtra are pointers to this possibility.

One could expect some moves from the government to address such concerns very soon.

Finally, the CSO data also points to another problem. As a CARE Ratings report points out, Private investment has been falling in gross capital formation. In fact, gross capital formation is itself declining. The report says, “The investment rate measured as the ratio of gross fixed capital formation to GDP at current prices is expected to decline further to 26.4% this fiscal from 27.1% last year and 34.3% in FY12. This indicates that corporate have not been investing in capital creation this year. A pick up private investment is essential for a rise in overall investment rate.”

But investment needs a good economic climate. At the moment most businessmen are wary about the government (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2016/08/arbitration-awards-india-shaken/). Foreign investors too are skittish. The government’s moves to discourage international arbitration – especially where the seat of arbitration is outside India – has upset many investor countries. That is another area that will need to be addressed.

COMMENTS