The Supreme Court ties itself up in knots over death with dignity

RN Bhaskar

“A calf, having been maimed, lay in agony in the ashram and despite all possible treatment and nursing, the surgeon declared the case to be past help and hope. The animal’s suffering was very acute.

In the circumstances, I felt that humanity demanded that the agony should be ended by ending life itself. The matter was placed before the whole ashram. Finally, in all humility but with the cleanest of convictions I got in my presence a doctor to administer the calf a quietus by means of a poison injection, and the whole thing was over in less than two minutes.

“Would I apply to human beings the principle that I have enunciated in connection with the calf? Would I like it to be applied in my own case? My reply is yes. Just as a surgeon does not commit himsa when he wields his knife on his patient’s body for the latter’s benefit, similarly one may find it necessary under certain imperative circumstances to go a step further and sever life from the body in the interest of the sufferer”.

Mahatma Gandhi on the Right to Die with Dignity (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2011/03/512/)

The apex court appears to be uncertain about the right to die with dignity. This is the third time in recent years that the country has actually touched on issues like the Living Will and passive euthanasia. These are issues that are extremely dear to people who believe that people have a right to decide how they should be allowed to be treated, or even how to die. Disclosure: the author is honorary secretary with the Society for the Right to Die with Dignity (SRDD).

In fact the Supreme Court made its recent observations in response to a petition by Common Cause to make the Living Will legal(https://static1.squarespace.com/static/551ea026e4b0adba21a8f9df/t/59de0c5e6f4ca380969e1d13/1507724391489/Submission_Vidhi_Advance_Directive_SC.pdf). SRDD is an intervenor to this petition, and also prays for granting legality to the Living Will (In fact Common Cause has a petition before the Supreme Court to make legal the concept of a Living Will.

The first time when the Supreme Court referred to the Living Will was in 2011 when the apex court was called upon to decide whether Aruna Shanbag, a nurse at KEM Hospital in Mumbai (who eventually died in September 2017) should be allowed to die a peaceful death instead of being kep alive through external support mechanisms.

The second time was when the government itself – through the Law Commission — put across a paper (http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report241.pdf) titled “Passive Euthanasia – A Relook. Report No.241. AUGUST 2012”

The second time was when the government itself – through the Law Commission — put across a paper (http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report241.pdf) titled “Passive Euthanasia – A Relook. Report No.241. AUGUST 2012”

The recent pronouncements of the Supreme Court were the third such instance.

The Aruna Shanbag case

The Supreme Court first touched upon the Living Will and Passive Euthanasia on March 7, 2011, when deliberating on the vexatious issue of whether Aruna Shangag should be allowed to die. Towards the end of Para 9 (www.supremecourtofindia.nic.in/outtoday/wr1152009.pdf) the Supreme Court stated that the issues under consideration were

“1) We have no indication of Aruna Shanbaug’s views or wishes with respect to life-sustaining treatments for a permanent vegetative state (PVS)

2) Any decision regarding her treatment will have to be taken by a surrogate.

3) The staff of the KEM hospital [who] have looked after her for 37 years, after she was abandoned by her family. We believe that the Dean of the KEM Hospital (representing the staff of hospital) is an appropriate surrogate.

4) If the doctors treating Aruna Shanbaug and the Dean of the KEM Hospital, together acting in the best interest of the patient, feel that life sustaining treatments should continue, their decision should be respected.

5) If the doctors treating Aruna Shanbaug and the Dean of the KEM Hospital, together acting in the best interest of the patient, feel that withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments is the appropriate course of action, they should be allowed to do so, and their actions should not be considered unlawful.”

Implicit in the discussions was the thought that if Aruna Shanbag had left behind a Living Will, things could have been different on determining the course of treatment. But the court refused to state categorically that the Living Will had legal sanction.

The Living Will

The Living Will is nothing but an advance directive – made legal in many countries. It is a directive to the medical fraternity on what steps to take – or avoid – when the person concerned is in a coma or is unable to expressly spell out the course of treatment that should be permitted for himself.

It is based on a simple premise that every mentally competent individual has the right to decide what treatment to accept or reject. Thus even if I have a tumour which could be life threatening, and I refuse to take the treatment my doctor recommends for me, I am within my right to refuse such recommendations. This right remains undiminished even if I were to die because of my refusal to accept the recommended line of treatment.

But the situation changes when I am unable to express myself either because I am in a state of coma or PVS. At that point of time, the state takes over, and the doctors are free to treat me the way they wish. If my relatives and friends protest, and refuse the recommended line of treatment, they could be held as abettors in hastening my death.

It is to prevent such a situation that many countries have allowed patients to prepare an advance directive or Living Will (sample can be downloaded from http://www.asiaconverge.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SRDD_Living-Will_revised.pdf). It outlines the line of treatment a patient will accept or reject in case of inability to express this wish. To give it more teeth, many doctors and lawyers even recommend that the person executes a limited power of attorney authorizing someone to ensure that my Living Will is acted upon. If you look at this logically, the Living Will does nothing more than arming a person with the same rights he had when he was mentally competent and articulate. It asks for nothing more and nothing less.

The knots

Both the government and the Supreme Court have tended to tie themselves in knots over the issues relating to passive euthanasia and the Living Will.

For this author, the Living Will is nothing but an extension of the rights a person already enjoys. It only allows him or her to spell out clearly – in the presence of a witness – what line of treatment he/she would like to accept/reject once the person is in a state where such a wish cannot be expressed.

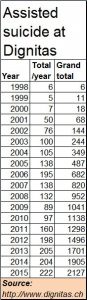

Passive euthanasia, in fact, goes a bit further. It authorises a third party to allow a person to die. Yet, many countries have already permitted passive euthanasia – the most prominent being Dignitas in Switzerland (http://www.dignitas.ch/). This is where patients from all over the world go, to seek a relief from life. At Dignitas too, the doctors examine the patient, so does a psychiatrist. If they conclude that the patient indeed faces no cure from pain and misery, it shows the patient how to end his or her life. Swiss laws permit this. Many other countries too permit this (including the Netherland and several states in the US) (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2016/05/euthanasia-debate-all-you-need-to-know-about-how-other-countries-dealt-with-right-to-die/). And despite alarmist forecasts that such measures would open the floodgates to suicides, the track record at Dignitas shows that this hasn’t really happened (see chart)

In all humility, and with no intent to run down the opinions of either the courts or the government, this author believes that the Living Will should be granted legality as a logical extension of existing laws.

The second too – passive euthanasia — is immensely desirable. The episode regarding Mahatma Gandhi’s decision to put a heifer to permanent sleep explains why.

The Supreme Court fears that both the Living Will and Passive Euthanasia can be misused. Respectfully, this author believes that anything can be misused – a matchstick, a knife, a scalpel, an icepick – the list is endless. Civilisations grow stronger when ways are found to prevent misuse, and not by banning such items. When fears are allowed to become bans, a civilization moves towards ossification, even fundamentalism.

THOA 1994

There is a second issue that the Supreme Court and the government appear to have overlooked. India already has in place another piece of legislation — The Transplantation of Human Organs Act 1994 (THOA 1994 http://health.bih.nic.in/Rules/THOA-1994.pdf). This Act permits a team to doctors to certify a person brain dead. Six hours later, another team checks the body once again. If both teams confirm that the patient is indeed brain dead, the body can be harvested for its organs for being transplanted into another body.

If euthanasia can be misused, so can THOA 1994. A patient in coma, who is not brain dead, may be declared brain dead by unscrupulous elements in society. The remedy lies in trust, good processes, appropriate safeguards and stringent punishment for any violation of the law.

Thus, the method the Supreme Court approved in the Aruna Shanbag case has resulted in al most no requests for passive euthanasia. The process is cumbersome. But THOA has permitted countless bodies to be cert9ified as being fit for organ harvesting.

The prescribed procedure for passive euthanasia is for a petitioner to approach the court with a request for allowing a patient to die. The court then appoints a panel of doctors, when then goes back to the court with its findings. The court then allows for apassive euthanasia, or rejects the petition. That could take months, even years.

One cynical reasoning is: THOA 1994 benefits recipients (which includes politicians and judges as well). Hence its processes have been simplified. Passive euthanasia benefits nobody but the patient, and maybe those who have to look after him/her. Hence the urgency for easing the processes has been ignored.

In fact, one of the finest descriptions of what the role of a doctor (Ior even society) should be has been expressed by the legendary Dr. Christian Barnard:

“lt is not true that we become doctors in order to prolong life, We become doctors in order to improve the quality of life, to give the patient a more enjoyable life . . . And the same is true when we are dealing with terminally ill patients: what we should ask ourselves is whether there is still any quality of life left. The doctor who is unconcerned about the quality of life is inhumane; and the real enemy is not death but inhumanity.”

Self-defeating laws lead to odd practices

When society does not permit the Living Will or even passive euthanasia, there are two unfortunate consequences. The first is where doctors and medical institutions can seek to benefit by prolonging the life of a person and earn fees from the process of such practices.

The second could be a bizarre manner of a patent’s family actually telling a hospital, “Yes, we agree that the patient must be saved and kept alive. Please go ahead and keep him alive. But we lack the money to pay the hospital. So you can proceed with the treatment you desire without recourse to us.”

Inability to pay for treatment is not a crime. Yet, not treating a patient is a crime. Finally, the hospital itself persuades the caretakers of the patient that there is no cure for the patient, and that the best way out is to allow him/her to be taken off ratification support systems, and taken home for the best palliative treatment possible.

In fact, many caring doctors do still manage to persuade families (very discreetly and privately though) to take care of the patient at home or in a sanatorium, because medical science can do nothing more for the patient. And in a country like India where the state refuses to take up the job of protecting and caring for the destitute, and caring for major incurable ailments could bankrupt families, the need for laws permitting the Living Will and passive euthanasia become crucial and urgent.

COMMENTS