http://www.firstpost.com/business/importing-pulses-to-maintain-buffer-stock-but-govts-move-at-times-hurt-domestic-producers-3433380.html

Pulse of the nation – IV

The govt’s power to permit import of pulses can sometimes hurt domestic producers

Part I – Introduction. Misplaced fallacies.

Part IV is about how short sighted India’s policy makers are. They were contracting import of pulses even in a year when output of pulses was meant to be good.

==========================

On 14 March 2017, C.R.Chaudhary, minister of state for consumer affairs, food and public distribution, told the Lok Sabha (in reply to unstarred question No.2059) that a shortage of pulses would continue to be experienced.

He said that the government had been advised through Niti Aayog’s Working Group Report on Foodgrains-Balancing Demand & Supply During 12th Five Year Plan that the projected demand for pulses during 2016-17 is estimated to be around 24.61 million tonnes (higher than 23.6 million tonnes of last year). In contrast, the estimated domestic production of pulses (2nd Advance Estimates of Production of Foodgrains, 2016-17) is 22.14 million tonnes (compared to 16.3 million tonnes last year). This could mean a shortfall of around 2.47 million tonnes.

He said that the government had been advised through Niti Aayog’s Working Group Report on Foodgrains-Balancing Demand & Supply During 12th Five Year Plan that the projected demand for pulses during 2016-17 is estimated to be around 24.61 million tonnes (higher than 23.6 million tonnes of last year). In contrast, the estimated domestic production of pulses (2nd Advance Estimates of Production of Foodgrains, 2016-17) is 22.14 million tonnes (compared to 16.3 million tonnes last year). This could mean a shortfall of around 2.47 million tonnes.

He also stated that “the Government has approved engaging a professional Buffer Stock Management Agency (BSMA) for efficient management of the buffer stock including procurement, storage, maintenance and liquidation of the stock as per Government directives from time to time. The agency for designing and managing the bid process has been selected. Contract for appointment is being finalized.”

He said that the government had approved the creation of a buffer stock of 2 million tonnes and that as on 8 March 2017, around 1.5 million tonnes of pulses had been procured for contracted for import towards building this buffer.

He said that the government had approved the creation of a buffer stock of 2 million tonnes and that as on 8 March 2017, around 1.5 million tonnes of pulses had been procured for contracted for import towards building this buffer.

He also said that the government has contracted imports of 4.06 lakh tonnes of pulses towards building the buffer stock. He explained that the prices of pulses fluctuates daily as well as over season. While approving the bid for imports, the Price Stabilization Fund Management Committee (PSFMC) compares the offer rate with prevailing domestic rates and bids are generally approved for import when the rate offered are lower than prevailing domestic prices of that pulses.

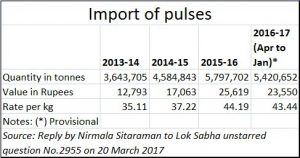

The answers sound immensely plausible. Then one gets the figures that Nirmala Sitaraman, minister of state, ministry of commerce gives out. The data showed that India had imported not just 2 million tonnes, but 5.4 million tonnes during 2016-17 (see table).

The answers sound immensely plausible. Then one gets the figures that Nirmala Sitaraman, minister of state, ministry of commerce gives out. The data showed that India had imported not just 2 million tonnes, but 5.4 million tonnes during 2016-17 (see table).

It is then that one begins to realise that the farmer’s anger has been fuelled by the government’s decision to continue allowing import of pulses.

Sitaraman did explain that the decision of the Government to import pulses towards building buffer stock is guided by domestic price and availability position. In view of the bumper production of kharif pulses, no import is being undertaken by the Government other than those already contracted when prices and availability position were difficult.

She said that for building a buffer stock of pulses, the government had through MMTC contracted import of 70,000 MT of Desi Chick Peas during 2016‐17 of which only 52,315 MT had arrived. The government had approved creation of buffer stock of pulses upto 2 million tonnes under Price Stabilization Fund (PSF). In addition, the government has signed a Memorundum of Understanding (MOU) with Mozambique for import of pulses on Government-to‐Government (G2G) basis during 2016‐17.

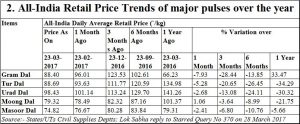

But, even after all such explanations are received, there are niggling worries about how prices for pulses get determined.

But, even after all such explanations are received, there are niggling worries about how prices for pulses get determined.

For one, there is no international price for pulses. It is a thinly traded commodity, consumed largely by India. It is India which decides the prices. When demand is high in India, and production is short of demand, India resorts to imports. At that time, international prices also go up. When India’s production is good, there is no big market for pulses grown overseas. International prices crash at such times.

This is amply evident from watching international prices and domestic prices over the past few years.

Second, while it is true that prices change from time to time, from country to country, and vary with the quantities imported, the numbers suggest that the price difference for any variety of pulses can be huge during the span of just one year.

One more interesting fact (see chart). While the government has contracted to import from Mozambique, at no time last year did Mozambique offer India the most favourable of prices. In fact, at times India paid Mozambique prices that were higher than the average international price for pulses during the year. The spread in prices of pulses can be anywhere between $200 to $900 per tonne during the year.

Third, unlike other commodities, India imports pulses from a variety of countries. No country produces pulses in huge quantities – though countries like Canada, Myanmar and Australia have an edge. Canada exported around $1.5 billion worth pulses to India last year, though this year will see this number fall because of India’s own increased production. In most cases, the growers of pulses in other countries are people of Indian origin. Or they are traders with excellent linkages with farmers in those countries. Hence they know both the markets overseas and those in India Just take a sampling of the countries from which India imported. The basket is huge. However, Australia, Canada and Myanmar remain the biggest sources for pulses import.

It is when one takes all these factors into account, that one realises that the government should have moved in earlier to impose customs duties on the import of pulses, if not ban them altogether. At the same time, the building of a buffer stock should be taken up through more purchases from domestic producers – preferably through an open reverse-auction system to promote transparency, and the taking of corrective measures to ensure that imports do not hurt domestic farmers. After all, even if one goes by the Niti Aayog figure that there will be a shortfall of around 2.4 million tonnes, it is difficult to justify import of 5.4 million tonnes.

Heeding to the clamour from farmers, the government finally imposed an import duty of 10% by the end of March, but only for urad dal. But there is already a demand for increasing this to http://smestreet.in/ram-vilas-paswan-hails-import-duty-hike-on-pulses/

Finally, there is an urgent need to introduce measures chich allow farmers to discover prices for puses three months and six months ahead of the harvesting season. But more of that in the next part.

COMMENTS