Epayment spells boom-times for financial intermediaries

Critics of demonetisation (and epayment) are quick to point out that the de-legalisation of high value notes could lead to a slowdown of the economy.

Maybe, it will.

But even then India’s GDP is likely to go up sharply, and not falter, within a year’s time. And the single contributing factor will be epayments. Even if jobs do not increase, epayments alone could add at least a couple of percentages to India’s GDP.

But even then India’s GDP is likely to go up sharply, and not falter, within a year’s time. And the single contributing factor will be epayments. Even if jobs do not increase, epayments alone could add at least a couple of percentages to India’s GDP.

Sounds strange? But then here are the numbers that suggest this.

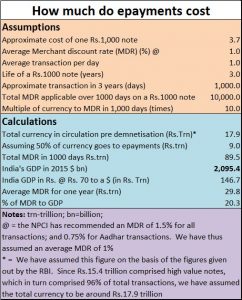

First, the assumptions:

Consider the table below, and look at the assumptions made. According to data available from the RBI, each Rs 1,000 note costs approximately under Rs 3.7 to print. Add to this other costs like transportation and storage and we could assume a total cost of Rs 6 per note.

The life of a currency note is a bit over three years, but we prefer to stay with the lower end of the range. So let us assume that the note will survive for three years. The cost of the note remains constant at Rs 6 per note.

Now turn to epayments. The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) has recommended a Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) of 1.5 percent for all transactions, except those which use Aadhaar linked accounts where the recommended rate is 0.75 percent. Currently credit/debit card companies charge anywhere between 2 percent and 3.5 percent. Merchant discount is the money a merchant pays to the credit or debit card company. Epayment services like Paytm do not charge an MDR, but when the money is sought to be taken out of the epayment wallet to be credited to any bank, Paytm charges around 5 percent. Hence we have taken an average MDR of just 1 percent.

Conventionally, a Rs 1,000 note accounts for one transaction a day. Thus in three years, which has been rounded off to account for 1,000 days, the total MDR of 1 percent will amount to around Rs 10,000 over a three year period. That gives us a multiple of 10.

For every Re 1, the average MDR will be Rs.10 in three years’ time, or Rs 3.33 in a year’s time. Do also bear in mind, that the velocity of currency for smaller denominations may be over 5 or 10 per day. But in order to be conservative in our approach, we have stuck to one transaction a day.

Then the calculations

We have assumed the total currency in circulation to be around 17.9 trillion. We have arrived at this figure by using the Rs 15.4 trillion given out by the RBI as comprising high value notes which got demonetised (or de-legalised). Since such notes accounted for 86 percent of total transactions, we arrive at the figure of 17.9 trillion.

We had a problem with GDP, since the Economic Survey gives GVA (gross value added) nowadays. So we took the figure used by the World Bank. For the year 2015, India’s GDP was around $2.1 trillion (2095.4 billion). Once again we decided to err on the side of caution and took an exchange rate of Rs 70 per USD. That gives us a GDP figure of Rs 146.7 trillion.

So far so good. We finally took one third of the total MDR calculated for 1,000 days, in order to get the MDR for just one year. And we got the figure Rs 29.8 trillion.

Take this figure as a percentage of India’s GDP, and you arrive at the conclusion that MDR alone could account for 20 percent of India’s GDP.

Does this mean that India’s GDP will swell by this astronomical number? Not really. There will be some savings of costs of accountants and of people who are employed to count the notes and reconcile the figures. There will be savings in the printing of notes, and in transporting and storing them. And there could be a few slippages here and there.

This means that the financial sector could benefit from earnings of as much as Rs 29.8 trillion annually. That could explain why every bank has jumped on the bandwagon for setting up e-wallets.

And there is also the possibility of the government itself stepping in and reducing MDR.

Whatever happens, the mere introduction of epayments will boost India’s GDP. However, if enough jobs are not created, there could be both political and social turmoil. And that could force a reduction in the number of transactions.

But then epayments could actually galvanise the number of transactions a day. That, in turn, could further boost MDR.

Either way, India has a lot to gain. Its GDP goes up, its tax collection base goes up. The government’s ability to mop up more money goes up.

The only variable is job creation. One only hopes that the government does something to make employment rates also go up.

COMMENTS