http://www.freepressjournal.in/pending-cases-and-political-criminality/http://epaper.freepressjournal.in/625996/The-Free-Press-Journal-Mumbai-Edition/29-Oct-2015?show=touch#page/10/1

Pending cases and political criminality

— By | Oct 29, 2015 12:50 am

There is one question most social scientists have been grappling with for ages – what is the difference between a government and the mafia? After all, both collect protection money, though the government may choose to call them taxes and cesses. The biggest difference, at least in developing societies, appears to be that the government collects money, but does not protect. The strongman collects money, yes. But he also protects.

Ideally, a government is supposed to provide speedy, effective and fair protection on the basis of law – where all people are equal before justice.In reality, something else happens in developing countries, especially in India. Ask a slum dweller what he would do in case some miscreants were harassing his daughter; would he go to the police to complain, or would he go to the local strongman, to seek redressal of his grievances?

Ideally, a government is supposed to provide speedy, effective and fair protection on the basis of law – where all people are equal before justice.In reality, something else happens in developing countries, especially in India. Ask a slum dweller what he would do in case some miscreants were harassing his daughter; would he go to the police to complain, or would he go to the local strongman, to seek redressal of his grievances?

In most cases you will find that the average slum dweller, even the common citizen, would approach the local strongman. Why? Because the police would harass the complainant a great deal, and find excuses not to register the complaint. It has become both inconvenient and predatory. On the other hand, the local strongman would immediately issue orders. His henchmen would approach the miscreants and tell them to lay off. If the suggestion wasn’t respected, the strongman would handle the situation by other means, including force.

For the slumdweller, therefore, the local strongman is the law enforcer, the one who dispenses justice more speedily. Naturally, when the strongman decides to contest elections, the slumdweller will vote for the strongman, and not for others. The strongman guarantees protection in better ways than the government can. Effectively, the illegitimate has become more legitimate. Conversely, the legitimate has become suspect. And that is where the criminalisation of politics begins.

Probe a bit deeper, and you will discover the reason why this reversal of roles has taken place. The main reason why the government has failed is because the courts – yes the courts more than any other arm of government – have failed to realise that for the small man, speedy and effective justice is what matters. He knows, almost intuitively, that any delay in justice is more power to the oppressor. The miscreants will molest his daughter, and then it does not matter if he will get justice after 20 years – if at all.

Had the courts hauled up the police, or put the government on notice, for not registering FIRs within a week, and a preliminary investigation report within a fortnight, and the matter be put up for hearing within three weeks, and verdicts for ‘petty’ crimes pronounced within 4-6 weeks, the slumdweller might have gone to the police to register his complaint.

Had the courts routinely hauled up the police for ‘harassment’ of complainants, the slumdweller might have been emboldened to approach the police. Had the courts been willing to ask the government to haul up policemen who prepare ‘loose’ and ‘leaky’ charge-sheets, often in collusion with the offenders, the slumdweller would have revived his confidence in the official legal system.

Delay in justice empowers the ‘illegitimate’ judicial process. The strongman remains the small person’s representative, even if he has criminal cases registered against him. The criminalisation of politics takes place because the courts have not moved fast enough. They have failed to use the arsenal already available with them to keep other arms of the government in check.

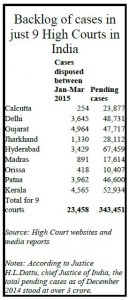

Look at the data. The chief justice of India anxiously pointed out, in December 2014, to the manner in which almost 3 crore cases are pending before Indian courts at various levels. The pendency has reached 64,919 before the Supreme Courts itself as on December 1, 2014.But why do courts delay cases? Well, that is a long and convoluted story.

The government does not clear appointment of additional judges, hence fewer judges are confronted with too many cases, thus causing a backlog. When the judges are cleared, there are not enough courtrooms and infrastructure for supporting staff. The executive and the legislature have also contributed to the mess the judiciary is in. And the courts permit too many adjournments.

Compounding this is the poor pay packages for judges. There have also been instances of judges behaving collusively. They have often turned a blind eye to aberrations in the dispensations of justice. The rich and the powerful are allowed to get away more lightly than the poor and the less privileged (http://www.freepressjournal.in/the-nexus-between-pockets-and-the-noose/).

But the judiciary could have prevented this rot when the first signs of rot began. It chose not to raise an alarm. It is only recently, that the judiciary has begun putting politicians and senior bureaucrats in jail and also exhorting the executive to stop protecting the guilty. After all, the court has the power to strike down any law which exempts the powerful from investigation or judicial action. That is violative of the cardinal principal that all men are equal before the law.

True, politicians and the executive won’t like this. They will brand it as ‘judicial activism’. But the country has a choice – to allow the spread of the strongman culture, or to reinforce the rule of law. The path is treacherous, and the responsibility tremendous. Hopefully, the courts will take their job a bit more seriously. But more on that next week.

The author is consulting editor with The Free Press Journal.

COMMENTS