https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/the-judiciarys-fabric-is-frayed-thanks-primarily-to-the-government

Without a strong judiciary, India’s legislators and bureaucrats will cripple India’s economic growth

(All other articles in the Judiciary series can be found at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/03/the-judiciary-series/)

RN Bhaskar

On February 13, 2021, former chief justice of India, Ranjan Gogoi called the state of the judiciary in India as “ramshackled”. He also said that if one goes to Indian courts the person would have to wait endlessly for a verdict (https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2021/feb/14/judiciary-ramshackled-going-to-court-is-useless-ex-cji-ranjan-gogoi-2263698.html), This could not be called a stray remark because it came from someone who was till recently chief justice of India.

The shocking absurdity of skin-to-skin

The tatters were in full view when barely 10 days ago, the government decided to extend the tenure of Judge Pushpa Ganediwala. Her extension was cancelled by the collegium of supreme court judges. This was on account of two shocking and controversial judgements she issued in January.

The judgements could have even diluted the POSCO Act which was meant to severely punish anyone trying to sexually molest a child. Her judgement almost set the culprit Scott free – but for the SC staying her judgement. She said that the accused had not really engaged in a skin-to-skin contact, and that touching through a cloth could not be called molestation.

The judgements could have even diluted the POSCO Act which was meant to severely punish anyone trying to sexually molest a child. Her judgement almost set the culprit Scott free – but for the SC staying her judgement. She said that the accused had not really engaged in a skin-to-skin contact, and that touching through a cloth could not be called molestation.

It defied a universal understanding of what constituted molestation, especially that of a child. Effectively, she was stating that a squeeze of a child’s breast, or a pinch on the bottom could not be called molestation because it was not skin-to-skin. It flew in the face of common sense. And yet the government gave her a one-year extension. These were judgements that should have compelled the government and the president of India to express extreme displeasure. They should have dismissed the person, even pressed charges of incompetence and worse against her, even if the collegium had actually recommended her case. That nobody dared dismiss her is difficult to comprehend. It will haunt the judiciary – even society – for exceptionally long years.

In these two recent developments, one had a horrendous and absurd interpretation of the law on the one hand, and a charge that cases take years to get redressed on the other. Clearly, something is terribly wrong with the dispensation of law, and with the judiciary. On the one side you have a continuation of the services of a person who has already exhibited signs of having lost common sense; on the other is a former chief justice who bemoans the current state of the judiciary.

That is why this article became important. Plus there was this incredibly brilliant discussion series (https://www.indiandemocracyatwork.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Pre-Conference-Booklet-Rule-of-Law-IDAW-.pdf) organised by Indian Democracy at Work on The Rule of Law (its advocacy paper can be downloaded from https://www.fdrindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Rule-of-Law-Advocacy-Paper.pdf). . Both the two disturbing events narrated above, and the conference, provided enough reason and information support to do this series on how attempts are underway to weaken, not strengthen, the judiciary.

Not enough judges

The first problem that ails the judiciary is that there are not enough judges in the country. There is no shortage of talent. But there is unwillingness on the part of the government to fill the vacancies quickly.

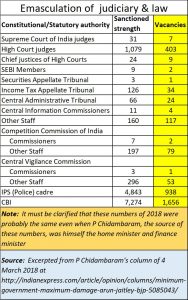

PC Chidambaram, at various times the finance minister, law minister and home minister of India, gave a compilation of numbers that tells you how dangerous the situation is. (see chart), He pointed out that successive governments had ensured that at least 30% of the judges and judicial posts are kept vacant (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/09/3-measures-can-stop-india-becoming-failed-state/). In other words, the legislators were preventing the backlog of cases to be cleared. It would, therefore, appear that they wanted to keep petitioners who had filed cases, and the judiciary, under pressure.

Not that the situation has improved under the current government. Just watch how the vacancies at the Supreme Courts and high courts also remain vacant (see chart). The Supreme Court vacancies are concealed because some more judges are to retire within the next few months. The vacancies will be larger if that is considered.

Not that the situation has improved under the current government. Just watch how the vacancies at the Supreme Courts and high courts also remain vacant (see chart). The Supreme Court vacancies are concealed because some more judges are to retire within the next few months. The vacancies will be larger if that is considered.

But look at the final tally of all seats for the Supreme Court and the high courts in India (as of February 2021). Once again, out of a total sanctioned strength of 1,090 seats for judges, there were 419 vacancies. In other words, 39% of the seats for judges remained vacant. How does any arm of the government function with just 60% of its sanctioned strength?

But this is just one part of the sorry situation. The sanctioned strength is itself a fraction of what it ought to be. Consider the next two tables.

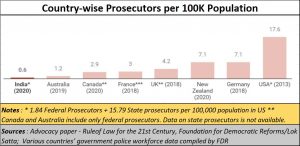

The one alongside is about prosecutors, who fight on behalf of the government, the police, and the administration to bring a culprit a justice. There is a shortage in the number of posts sanctioned for prosecutors. Thus, even if a suspect is arrested, he may have to wait for justice and the final verdict for a long time because there just aren’t enough prosecutors around. The strength of prosecutors in India compared to other countries in the world is pathetic. Does the government really believe is fair dispensation of justice?

The one alongside is about prosecutors, who fight on behalf of the government, the police, and the administration to bring a culprit a justice. There is a shortage in the number of posts sanctioned for prosecutors. Thus, even if a suspect is arrested, he may have to wait for justice and the final verdict for a long time because there just aren’t enough prosecutors around. The strength of prosecutors in India compared to other countries in the world is pathetic. Does the government really believe is fair dispensation of justice?

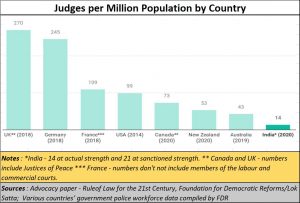

But the next chart should make a chill go down the spine. India does not have enough judges even as a percentage of the population. It is then that the realisation dawns that even the sanctioned strength is barely a tenth of what it ought to have been. This also means that the judiciary has been functioning with barely 10% of the judicial strength required.

But the next chart should make a chill go down the spine. India does not have enough judges even as a percentage of the population. It is then that the realisation dawns that even the sanctioned strength is barely a tenth of what it ought to have been. This also means that the judiciary has been functioning with barely 10% of the judicial strength required.

Cases pile up

Not surprisingly, as admitted by the government on 3 February 2021 (reported with annexures of Lok Sabha documents by Mint (https://www.livelaw.in/news-updates/judges-vacancies-high-courts-supreme-court-law-ministry-pending-cases-justice-169362) the number of cases pending before the Supreme Court had swelled from 57,346 in 2018 to 63,146 in 2020. The number of pending cases before high courts had similarly swelled from 44,48,926 in 2018 to 56,42,567 in 2020.

In 2015, the number of pending cases at high courts (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2015/10/is-political-criminality-just-inevitable-in-india/) was 3,43,451. It must be clarified though, that this data was only for nine courts in the country. However, there is no denying that current numbers point to the rapid decay in the judiciary abetted by the government.

Similarly, the government admitted that the number of pending cases had also gone up in District and Subordinate Courts from 29,173,911 as on 10 December 2018 to 37,183.419 as on 28 January 2021.

Can you ever have an Atma Nirbhar Bharat when the very props on which justice should stand are missing, or have been stolen?

Judges need longer tenures

Stolen is a harsh word, but when one looks at another issue, it all begins to sink in. Bureaucrats generally can serve out their entire career spanning 20-40 years unless there is a serious case of moral or professional turpitude. A politician can complete his full term of 5 years (unless there is a mid-term election called) and even stand for re-election. But many Supreme Court judges are not even given five years as their tenure.

Take the current batch of Supreme Court judges. Of the 30 judges listed on the Supreme Court website (https://main.sci.gov.in/chief-justice-judges) at least 11 judges have tenures that are less than five years, some less than two years. Even the current Supreme Court Chief Justice will have a tenure of just 1 year 85 days. Just imagine if legislators were given tenures of les than 5 years! Aren’t Supreme Court Judges meant to be at part with legislators. Why should the ministry of law and the collegium agree to give any judge a tenure of less than five years? How do they plan to bring about change in the dispensation of justice with noticeably short tenures?

In fact, chief justices should normally have a tenure of 10 years, so that they can concentrate on improving on the dispensation of justice. The date of retirement should not matter for them in much the same way as there is no date of retirement for legislators.

Why should legislators and bureaucrats have longer tenures than judges when it should be the other way around? The judiciary is the final bulwark of any civilisation. It has the power to strike down a bad piece of legislation or a rotten executive order. Are these attempts to reduce the numbers of judges to be interpreted as ways to make the judiciary ineffective and ineffectual? Could this be mere myopia? After all, there is little chance of economic revival without a strong judiciary.

This is a frightening thought. And such fears get reinforced as one looks at other aspects of the law and justice scenario. But more a bit later.

COMMENTS