https://www.firstpost.com/business/in-easing-agri-markets-and-movement-of-produce-nirmala-sitharaman-has-reiterated-earlier-promises-here-are-seven-more-urgently-needed-reforms-8374021.html

Atma Nirbhar – Agri-markets: A promise here and a promise there, with little in between

RN Bhaskar – 16 May 2020

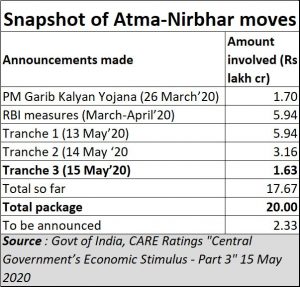

In terms of outlay, it is not as ambitious as most other schemes. It is only Rs.1.63 lakh crore (see table). In terms of dreams and promises, it could be the most seductive proposal ever. Considering that rural India accounts for almost 50% of the votes, the need for enticement is great. But the intent? Well, that is something only time will tell.

In fact, many of the schemes outlined on 15 May, 2020 have been spoken of and even announced at various fora by key government spokesmen. It was articulated by Prime Minister Modi even before 2013 when he was still chief minister of Gujarat.

In fact, many of the schemes outlined on 15 May, 2020 have been spoken of and even announced at various fora by key government spokesmen. It was articulated by Prime Minister Modi even before 2013 when he was still chief minister of Gujarat.

It was stated as part of the maiden budget of the late Arun Jaitely (as finance minister) in July 2014. He had then stated that “the Central government will work closely with the state governments to re-orient their respective APMC Acts, to provide for establishment of private market yards/private markets. The state governments will also be encouraged to develop farmers’ markets in town areas to enable the farmers to sell their produce directly.”

It was also echoed by current finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman in July 2019 (her maiden budget) — “The Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act should not hamper farmers from getting a fair price for their produce.” May 15, 2020, was therefore a refresher course.

In between, there were several other similar promises and assurances. Yesterday, these were reiterated.

In reality, little has been achieved. Except for milk, wheat and rice, and maybe spices and coffee (which have an altogether different marketing structure) all other crops languish. The vegetable grower gets barely 10% of the market price, while the milk producer can get as much as 80-85% of the market price. Rice and wheat farmers are pampered by very power political lobbies. Thus, they remain the only crops with a procurement mechanism through the Food Corporation of India (FCI), and farmers get almost twice the international price for this produce. But more on this later.

Three axioms

To understand why these dreams are often bandied around, one must first study India’s boldest, and the best, agricultural experiment – the one ushered in by Verghese Kurien as Operation Flood. Thanks to the vision of Lal Bahadur Shastri, the then prime minister, NDDB was transferred to Amul’s care, and got headquartered in Anand, Gujarat. Kurien had just three axioms (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2013/05/strategic-vision-kurien-style/) .

First, the producer (farmer) was more important than either the processor or the distributor/marketer, hence deserved a higher share of the market price than the others.

Second, farm prices must remain protected. There is no such thing as market competition, because each country could subsidise exports. He therefore was totally against imports. All gifts, aid and even import of milk aid had to be done through NDDB, which would then sell them at market prices, not allowing farmers to suffer a fall in market prices. The profits were used by NDDB to promote dairy development. Thus without any subsidies, milk became a formidable industry, albeit under the cooperative umbrella.

The third axiom was that India must adhere to production by masses, and not mass production. He was aware that most farmers had 1-5 cows in their backyard. A mechanism had to be created to collect their milk, process it, and then market it. Surplus milk was processed further into skimmed milk powder (SMP) and other dairy products giving it a longer shelf life. SMP was reconstituted into milk in months when milk production was poor. The farmer did not suffer a fall in milk prices. Confident of this safety net, more farmers got into producing milk in these ‘protected’ areas, and India became the world’\s largest producer of milk.

Like milk, like agriculture

Like milk, Indian agriculture is characterised by small and medium farmers. They need protection against any fall in domestic prices. They need a marketing mechanism which could take care of surplus production and prevent prices crashing, and also prevent imports and thus damage the value of their year-long labour.

Like milk, agriculture is in the grip of middlemen who also often act as advisors and moneylenders to each rural family. They control the price that is paid to farmers, who in turn are left with no choice. When the APMCs were created, it was to break the stranglehold of these middlemen. But middlemen got close to politicians, and together they controlled the APMCs, which became a bigger and more lethal exploiter.

Kurien knew the pernicious power of middlemen and politicians (and wily bureaucrats too). All of them were banned from participating in the milk business in Gujarat – the home of the milk revolution. The three hated Kurien for this, and he happily returned that sentiment.

But politicians saw the tremendous money and voting power in harnessing milk producers. So they set up their own cooperatives in Maharashtgra. In Andhra Pradesh, Chandra Babu set up his own corporate milk company under the name Heritage. Both are not as good with farmers as the Amul group. Responsible private players like Hatsun (India’s largest privat4e sector milk company) also pay farmers well.

Lately, the government has tried to break up the milk industry to reap political dividends. It did so last year by almost okaying the RCEP proposals (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/10/milk-and-rcep/) for allowing dairy imports. It then allowed subsidies for milk, which could usher in politicisation and favouritism (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/02/verghese-kuriens-milk-model-curdled/). Milk remains the only agricultural produce which has remained healthy without subsidies. Don’t destroy it.

So when the government talks about making farmers independent, it must be looked at cynically. Politicians quickly master the fine art of saying one thing and doing quite another.

The new proposals

Of the 11 announcements, three concern governance and administrative reforms (the author calls them dreams), including amendment of the Essential Commodities Act (ECA), 1955, and agriculture marketing reforms through a Central law.

Others include

- a Rs 1 lakh crore Agri Infrastructure Fund

- formalisation of Micro Food Enterprises, with an outlay of Rs 10,000 crore;

- a vaccination drive against food and mouth disease among cattle (something which NDDB has been doing for the past five years)

- extension of the Operation Greens from tomatoes, onion and potatoes to all fruits and vegetables

- help for fishermen through the Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana; a Rs 15,000-crore Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund

- a Rs 4,000 crore outlay for promotion of herbal cultivation, and

- a Rs 500 crore scheme to promote beekeeping.

But if the government really wanted farmers to benefit, it should have done some of the following:

First, ensure that all FCI procurement of rice and wheat take place through MCX, NCDEX and other commodity exchanges. This will ensure that marginal farmers producing rice and wheat are not left out by the FCI, and then compelled to sell at distress prices. FCI is known to favour larger and politically connected farmers. Such a move would also prevent the FCI from offering first grade prices for second grade crop (stocks are never audited or assayed by third party evaluators). That explains why a lot of grain is allowed to rot as it erases all evidence of wrongful payments. All this will benefit farmers, and make the commodity exchanges stronger. It would help root out corruption as well. But the government is unlikely to do this because of huge political payoffs and interests.

Second, get the WDRAI (Warehousing Development and Regulation Authority of India) to transfer all state and government godowns and warehouses (including those of the FCI and the state warehousing corporations) to affiliates of commodity exchanges, or to farmer producer organisations. That will bring in greater transparency in stocks held, and warehousing capabilities (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/02/budget-2020-warehousing-great-idea-linkages-need-fixed-make-work/).

Today, the WDRA refuses to even mention the storage capacity of warehouses in the country (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/08/is-wdra-a-functioning-organisation/), despite several email and telephonic reminders. This is concealment over opaqueness.

Third, empower select FPOs with huge funds to set up large scale processing plants in specific areas. For example there could be one in an onion growing area, another in a potato growing area, and several smaller ones in tomato and chilliy growing areas and so on. This way, you could replicate a weaker version of the Amul model, but with processing and marketing controlled by farmers. Unless farmers are actually empowered, they will be decimated by politicians and middlemen-traders.

Fourth, put a ban on all import of agricultural produce, unless approved by a majority of the FPOs. That will prevent a pulses crisis (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/05/how-pulses-imports-drove-domestic-growers-to-the-ground/). Or even a milk powder import possibility.

Fifth, desist the temptation to offer subsidies selectively. If required, empower FPOs which will then create a market development fund.

Sixth, there is little mention about hydroponics (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/06/hydroponics-could-be-the-future-of-farming/), the only solution to unseasonal rains and climate change. It could be the best solution for growing Ayurveda crops as well.

Seventh, the mention of the lucrative seaweed farming potential has been ignored (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/06/harvesting-seaweed/). Ditto with growing fish – not on land-based fish farms, but in international waters — like Norway does, with onboard processing capabilities in giant fishing trawlers (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/10/garware-technical-fibres-could-transform-agriculture-and-fisheries-in-india/). Fund fishing cooperatives to move into this area, so that catchment areas are never depleted (fish is farmed, not exploited, in the deep seas).

To summarise, the government’s proposals look good, but the vision is missing. The promises of change were made before, they are being made again. And the way the government has tried to break up the milk industry leaves observers worried about the commitment of the government to Atma Nirbhar farmers.

COMMENTS