http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/is-your-job-at-risk-from-the-onward-march-of-the-robots-2423527.html

Is your job at risk? Will robots make you redundant?

RN Bhaskar -Oct 30, 2017 05:21 PM IST

The danger to jobs has always been round the corner during key moments in history. Yet, in each case, the fears turned out to be more illusory. The world moved on. New types of jobs kept on getting created.

The topic that gripped the attention of almost everyone at the recently concluded World Economic Forum – or WEF — was whether anyone could safeguard jobs any more. Jack Ma of Alibaba raised the ante even higher when he said that even the jobs of CEOs could be at risk from automation.

The ghost of joblessness was the most traumatic when desktop computers began being introduced in offices. Almost all clerical staff thought that their jobs were at risk. In India, bank labour unions were powerful enough to stave off computerization by almost a decade.

Yet, in each case, the fears turned out to be more illusory. The world moved on. New types of jobs kept on getting created.

New ghosts. New fears.

But the jitters came back by 2015. That was when smart computers began doing some of the jobs that humans used to do. The age of robots had just begun. Unlike factory robots which remained confined to factory workshops, these were robots that could move around your homes, restaurants, roads and even offices. Their numbers too were large enough to threaten – if not actually replace — all types of jobs. You had tiny robots that could be sent into drain pipes to clean the sewers. You had miniature robots to travel through the insides of bodies as well. And now you were beginning to see humanoid robots that could walk, talk and even work like humans.

The fears were large enough for Bloomberg to come up with an article in end-December 2016 to ask the dreaded question: will your job be at risk.

The saving grace then was that jobs that were more mechanical in nature could be at risk. But jobs which required intelligence, and were non-repetitive in nature could be considered safe. Hence, Bloomberg predicted that jobs for sociologists, lawyers, CEOs, financial advisors., etc were not likely to be as at risk as, say, the jobs of drivers, plumbers and roofers (see Graph 1).

The saving grace then was that jobs that were more mechanical in nature could be at risk. But jobs which required intelligence, and were non-repetitive in nature could be considered safe. Hence, Bloomberg predicted that jobs for sociologists, lawyers, CEOs, financial advisors., etc were not likely to be as at risk as, say, the jobs of drivers, plumbers and roofers (see Graph 1).

That fitted in well with news about driverless cars, pilotless planes, trains without drivers, and robotized waiters serving dishes to customers in restaurants. This time, the jobs that could be affected could be many more – especially for countries like India which have tens of thousands of people employed as drivers both in their home countries as well as overseas.

Taxi drivers fear the worst for their jobs because the new generation of cars would be pods which would pick up waiting passengers from their locations and take them to the destinations they have marked in their applications. There would be no driver, no need to speak to anyone — a silent drive from pickup point to destination.

AI and Robotics

The issue was serious enough to be taken up at the recently concluded WEF. The topic “Artificial Intelligence and Robotics” turned out to be compelling and worrisome. That is where Jack Ma frightened almost everyone out of their wits by stating that even CEOs had cause to worry. Ma believes that companies must be prepared for decades of pain to come to terms with the advance of robots. This sentiment was reinforced by the president of the World Bank who believes that robots have put the entire world on a dangerous path.

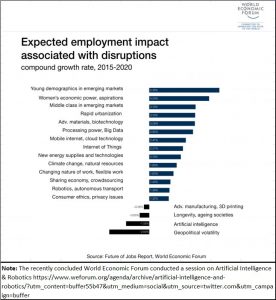

So are all jobs at risk? Not really. But the factors impacting jobs will be many (see Graph 2). It could be the increased power of computing, or the emergence of a large middle class which was willing to try on new gadgets – expect the robot at home to become a status symbol initially – or even urbanisation. Collectively, they make the petri dish rich enough to incubate robots.

Obviously, countries will have to navigate carefully, to find ways to ensure that job formation efforts do not flag. They will have to ensure that the adverse impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and robotics are minimized as far as is possible – at least for the short term. In the long term, it will depend on how fast robots adapt to the new demands of the market, and how rapidly humans come up with newer ideas than robots can.

In reality, as in the past, there are chances that humans will come up with new concepts and new jobs. A case in point is Germany. It has many more industrial robots than even the US – and has not faced job losses. By 2014, there were 7.6 robots per thousand German workers, compared to 1.6 in the US. Germany has managed to stay ahead of the curve. It has come up with more innovations and concepts than can be mastered by robots overnight.

In reality, as in the past, there are chances that humans will come up with new concepts and new jobs. A case in point is Germany. It has many more industrial robots than even the US – and has not faced job losses. By 2014, there were 7.6 robots per thousand German workers, compared to 1.6 in the US. Germany has managed to stay ahead of the curve. It has come up with more innovations and concepts than can be mastered by robots overnight.

Winners and losers

So who are the gainers and losers in the advance of AI? According to PWC, the biggest beneficiary will be China (see Graph 3). It knows that its one child policy (jettisoned recently) will cause its population to age very soon. Rather than depend on imported workers, or see its global market share slipping, China has decided to adopt robotics more aggressively than any other country.

For instance, unwilling to lose its Numero Uno position in garment exports, it wants to introduce robots for as many processes as possible so that he does not get edged out by increasing labour costs at home. Its philosophy is clearly – I would rather have my robots compete with me, than have another country compete for my markets. Will such a strategy succeed? Nobody knows. But it is a clever – albeit dangerous – model to adopt. Maybe, China will also begin exporting robotised waitresses to the entire world!

That could explain why PWC expects 26 percent of China’s GDP coming from AI and robotics. This would be closely followed by the US (14.5 percent).

Mass production vs production by masses

Of course, this would assume that global business would be dependent on mass production. But that might not be the case. Germany has showed how markets can be won through customized products and services. Not surprisingly, Germany has almost 6.6 percent of its GDP coming through exports. Compare this with 3.5 percent for China.

Germany’s exports come from micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). These companies offer the world products that do not have a market for large numbers, but are extremely sophisticated – even customized — and are demanded by countries in small numbers. That is clearly the strategy India too may want to adopt.

In the coming decade, India may have to work on several policy initiatives. One of them will be to realise that it will not be able to stave off automation (even in jobs for drivers) for too long. It will, therefore, have to focus on new job opportunities. It will have to plan on disruptions that make older models of growth impossible to protect or promote. The need for good school education will, therefore, be crucial.

One way in which India can create huge numbers of jobs – both directly and indirectly – is by adopting a new model for distributed solar and methane clusters. By creating a middle layer to install, maintain and regulate decentralised power generation and gas supplies, India could achieve two objectives. It could create around 83 million jobs directly and indirectly — enough for at least 6-7 years (assuming a minimum demand for 12 million jobs each year). It could also see a reduction in imports, which then could be used to promote skills development and school education. Small numbers will matter.

The other way is to focus on the Verghese Kurien model of production by the masses, not mass production. Focus on infrastructure, super efficient processing and marketing. Never let the farmer face distress through plummeting prices. And keep the customer happy. Not surprisingly, Kurien managed to make India the largest producer of milk in the world.

It may be worth recalling that one reason why Indian fabrics got exported in very large numbers is because it can offer countless designs in small runs. That gives customers greater variety, more exclusivity, and at reasonable prices. China, too, hasn’t been able to dent this market as yet.

Therefore, the focus will have to be on reinvigorating a shattered and pulverized school education. It means revamping India’s skill development, which remains in a time warp in most places. Most of all, it means rejuvenating the MSME sectors.

If India can do all this, it can withstand the onslaught of AI and the robots. If it cannot, expect a lot of pain to follow.

COMMENTS