http://www.firstpost.com/business/how-to-protect-indias-agriculture-sector-from-over-zealous-govt-functionaries-3435752.html

Pulse of the nation – V

Pulses and some simple ways to protect India’s agriculture

Part I – Introduction. Misplaced fallacies.

Part V talks about the need of a sensible policy which allows pulses and millets to find a place in the sun both in terms of sunlight as well as sustained earnings.

=================

If there is any sector which the government of India is focused on, it agriculture. Linked to it is, of course, the rural sector. There are several reasons for this.

First, almost 50% of India’s population dwells in rural areas and are directly influenced by agricultural prosperity. These people are also keen voters, less apathetic than urban folk. In fact, if the electoral results of 2014 are analysed, the contribution of the rural sector to BJP’s victory was not insignificant. Hence, both politically and economically, focusing on this sector makes immense sense.

Secondly, the rural sector is in such a poor state – except for fat-cat farmers who enjoy excellent linkages with politicians – that every rupee invested in this sector is likely to yield richer dividends that in urban sectors.

Third, rural prosperity is bound to reduce the pressure on urbanisation. Chances are that villages will begin to upgrade into towns and towns into cities, thus reducing the influx of people into already overstretched metropolises.

That could explain the government’s decision to double rural incomes by 2022.

But intentions are just plans. And as the saying goes, the path to hell is often paved with good intentions. Unless intentions are translated into well planned implementation, they become a travesty, a joke.

That is why, it is quite conceivable that the government has begun thinking of pruning the entire agricultural procurement and distribution apparatus. Take for instance two pieces of legislation that could come in quite handy.

Two legislations

First, on 14 March, 2017, R.C.Chaudhary, minister of state, consumer affairs, food and public distribution, stated (in reply to Lok Sabha unstarred question No.2059) that the government had approved engaging a professional Buffer Stock Management Agency (BSMA) for efficient management of the buffer stock including procurement, storage, maintenance and liquidation of the stock as per Government directives from time to time. The agency for designing and managing the bid process has been selected. Contract for appointment is being finalized.”

It is not yet known if this agency will supervise the workings of the Food Corporation of India (FCI), but it appears that the government is determined to restructure the laky systems of both the FCI and the public distribution system (PDS).

Taken in conjunction with an earlier piece of legislation, the WDRA, the results can be startling. It may be recalled that the government had on 25 October, 2010 notified the Warehouse Development & Regulation Act (WDRA) 2007 (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2010/12/warehousing-act-farm-game-changer/). True, the piece of legislation had been passed three years earlier. But it was not notified. Then, possibly under pressure from the Supreme Court of India which was furious at the callous manner in which grain was allowed to rot by the FCI, this piece of legislation became law. It may also be recalled that the Supreme Court then had stated that if the government cannot preserve the grain, give it away free to the poor, rather than to allow it to rot.

Taken in conjunction with an earlier piece of legislation, the WDRA, the results can be startling. It may be recalled that the government had on 25 October, 2010 notified the Warehouse Development & Regulation Act (WDRA) 2007 (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2010/12/warehousing-act-farm-game-changer/). True, the piece of legislation had been passed three years earlier. But it was not notified. Then, possibly under pressure from the Supreme Court of India which was furious at the callous manner in which grain was allowed to rot by the FCI, this piece of legislation became law. It may also be recalled that the Supreme Court then had stated that if the government cannot preserve the grain, give it away free to the poor, rather than to allow it to rot.

To understand the WDRA, it may be best to quote from its own presentation made to key officials of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) last year (http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/rap/files/meetings/2016/161109_AMIS_2.2-AMIS_Seminar_India-_WDRA_ppt.pdf). In that presentation, the WDRA had stated that

- Before the enactment of the WDRA, 2007, the warehouse receipt did not enjoy the fiduciary trust of the depositors and the banks.

- There were fears of non-recovery of loans in events, such as fraud, or mismanagement by the warehouse or insolvency of the depositor.

- The available legal remedies were inadequate and also time-consuming. The format for negotiable warehouse receipts was not uniform.

- Hence, there were impediments in the negotiability of warehouse receipts creating difficulties for the farmers and depositors of the goods.

- With the enactment of the WDRA Act 2007, the negotiable warehouse receipt issued by the registered warehouses has become a fully negotiable instrument.

- Backed by a Central Legislation, it can be traded as well as endorsed by the holder of the receipt.

- A uniform format of the negotiable warehouse receipt has been finalized in consultation with the Indian Banks’ Association and other stakeholders. The format has been printed by the Security Printing and Minting Corporation of India Limited which prints currency notes and other high security documents for the Govt. of India.

- The NWR format has unique features, such as anticopy, endless text, fine line pattern, micro-printing with rainbow coloring etc.

What the WDRA hopes to do is to empower the farmer in ways that had not been possible earlier. First, it would allow any marginal farmer to take his crop to the nearest authorized warehouse and hand over his crop to it. The warehouse, in turn identifies it (what, rice, urad, moong etc), gives it a grade (A or B or C grade), weighs it and then gives the farmer a receipt stating the kind of crop, the grade and the quantity. This negotiable warehouse receipt can then be given to the bank in return for cash. Prices are determined by checking the quotes on the commodity exchange.

Alternatively, the warehouse receipt can be sold through the commodity stock exchanges. The farmer thus has options before him. He can sell on a spot delivery basis, or opt for a future date of delivery as prices might be higher then.

The purchaser takes the receipt and picks up the grain from the authorized warehouse nearest to him for the quantity and grade mentioned in the receipt. Thus the purchaser can pick up the crop conveniently, and the farmer can sell his crop easily as well. The farmer also has the choice of keeping the receipt with him till such a time that he might choose to sell it.

The problems

As plans go, the above schemes are wonderful. But there are problems. First, warehouses come under state governments, and it is still not clear whether the warehouse will have to be certified by the WDRA or the state government or panchayats.

Second, there aren’t enough warehouses. The present numbers of warehouses do not provide easy access to all small farmers.

Third, unless and until FCI’s stocks are also put in authorised warehouses, the volumes just won’t be there to ensure viability. Will the government do this?

Fourth, unless the warehouse receipts are dematerialised, there is the possibility of scams taking place. Remember how even stamp papers brought out by the security press were forget? That was the Telgi scam. Dematerialised receipts do not require too much of sophistication in the way they are printed. They can be verified online. When linked with Aadhar, there is better transparency and security.

Fifth, the government has not yet come up with the process of assaying crops and insuring them in the warehouses. Each warehouse must have an assayer who knows how to value and weigh the crop – some farmers soak the grain before they bring it to the market-place so that they are heavier. A system of penalties that are swiftly meted out is sorely required.

What is not being done

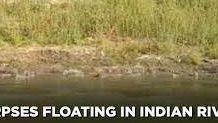

The above schemes are good. But it would appear that the intent to implement them is missing. Take the storage of wheat and rice. Each year, millions of tonnes of wheat and rice get damaged because they are not stored properly. As explained earlier, the government does not have enough warehouses to store the wheat and rice procured.

Ideally, the government should be putting out a notification that any wheat that cannot be stored must be sold on the commodity markets within 1 week of the new crop being procured. The system that should be followed should be first-in-first-out (FIFO).

Ideally, the government should be putting out a notification that any wheat that cannot be stored must be sold on the commodity markets within 1 week of the new crop being procured. The system that should be followed should be first-in-first-out (FIFO).

Thus old grain gets sold first, and new grain gets stored. This way, all the old grain the warehouses can be evaluated and cleared, and it will be possible to determine if the price realised in the market was the same as the one given for such grain. Within two years, the rotting of grains will get eliminated, and the potential of scams (paying first grade prices for second grade grain) almost eliminated. When the government needs additional grain, it can re-purchase the grain from the commodity markets. But this will require building of modern warehouses – where grain can be stored from the top and evacuated from the bottom (see pix). The Australian Wheat Board had initiated the building of such warehouses on a pilot basis a few years ago, but nothing happened thereafter .

Commodity markets help solve this problem. Using them, the government can transfer the cost of warehousing to the markets. True, it will lose some money. But losing 10-30% of the value of grain is preferable to losing 100% of the value which is what happens when the grain becomes rotten.

It is not known why the government has not done this as yet.

All warehouses should be told to reserve at least a quarter of their capacity for pulses and coarse grains. That way, the growers of pulses and coarse grains can discover market prices on the exchanges and can use the warehouses to sell their produce. It takes them away from the clutches of intermediaries.

But the lot is being done as well

But that is not to damn the government. Some amazing work is being done as well. For instance, even under the WDRA, “The Authority has so far notified 123 agricultural commodities including cereals, pulses, oilseeds, spices, dryfruits, tea, coffee and rubber etc. as per the standards prescribed by the Agmark, or other approved grading agencies for issuing Negotiable Warehouse Receipts. Besides, 26 horticultural commodities have also been notified for issuance of NWRs by cold-storages. “

WDRA states that it has already registered 1,299 warehouses (with storage capacity of 57.80 lakh tonnes). These warehouses also include 439 commodity-exchange-linked warehouses located in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat. How soon it will go beyond these (BJP ruled) states has yet to be determined.

Then there are other measures that are being taken. As mentioned by Sudarshan Bhagar, minister of state in the ministry of agriculture and farmers’ welfare (in reply to Lok Sabha unstarred question no 6200 on 11 April 2017), scientists of Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) are involved in research to develop the new varieties of pulses crops. A total 19 high yielding varieties of pulses including 6 of pigeon-pea, 5 of urad-bean and 8 of moong-bean have been developed by BARC to date.

He also stated that the government had taken several steps to increase the production of pulses. Under the National Food Security Mission (NFSM) programme, four projects have been sanctioned during 2016-17 by the Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare to boost pulses production in the country. These programmes are

- Creation of Seed-Hubs for increasing pulses production,

- Enhancing Breeder Seed Production for increasing Indigenous production of pulses,

- Cluster and front line demonstrations, and

- Creation of bio-fertilizers/bio-pesticides production centres. Further, Government has also implemented mini kits programme for quality seed distribution of pulses. In addition, minimum support price of major pulses have also been increased substantially.

A few days earlier (on 11 April, 2017) SS Ahluwalia, minister of state in the ministry of agriculture and farmers welfare had stated (in reply to Lok Sabha unstarred question No 6185) that four initiatives were underway. They involved ICAR, Indian Institute of Pulses Research (IIPR), Kanpur , three All India Coordinated Research Projects (AICRP) covering major pulses and one Network Project on arid legumes. All of them were engaged in developing location specific high yielding varieties and integrated crop production technologies.

In addition to these, several ad hoc research projects involving Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) (see URL) & Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Institutes are in operation to carry out basic and strategic research. He said that Under National Food Security Mission (NFSM) and Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) programmes, latest crop production technologies are being promoted through cluster demonstrations at farmers’ fields including assistance for various critical inputs like integrated nutrient management, integrated pest management, water saving devices, farm implements/ tools and cropping system based training to farmers by State Governments and ICAR Institutes including Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs).

In addition to these, several ad hoc research projects involving Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) (see URL) & Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Institutes are in operation to carry out basic and strategic research. He said that Under National Food Security Mission (NFSM) and Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) programmes, latest crop production technologies are being promoted through cluster demonstrations at farmers’ fields including assistance for various critical inputs like integrated nutrient management, integrated pest management, water saving devices, farm implements/ tools and cropping system based training to farmers by State Governments and ICAR Institutes including Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs).

But key to all these initiatives will be the government’s ability to ensure that all import is monitored very carefully to prevent dumping of grain in the markets. The last thing a farmer wants is that market prices get distorted by import. Agriculture is a very patient business, and unless it is protected from rash import, India will suffer. This is partly what happened with pulses this time.

Second, unless the farmer can discover future prices, he will be reluctant to grow specific crops. A minimum Support Price (MSP) mechanism is one way to achieve this. Another – and better way – is to have a very well governed commodity market. Unfortunately each time prices became speculative, instead of imposing margins and slowing down speculation, government have opted to banning trade in specific commodities. Any banning of trade hurts both the trade as well as farmers. Somehow, government officials have not learnt this as yet. In fact, even in the National Spot Exchange (NSEL), the problem became serious because of a banning of trade, not by slowing down speculation through the imposition of margins.

Lastly, it must be noted that even farmers need a rate of return. And this depends on both the price at which he can sell his crop, and his ability to reach the markets in time. Equally, it means mitigating risks.

Thankfully, the government, in January 2016, launched the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) – see http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=155033 . As Ashok Gulati, noted agronomist, puts it, “For the first time, farmers’ share of the premium was pegged at 2 per cent for kharif crops and 1.5 per cent for rabi crops. As a result, the area covered under insurance increased from 27.2 million ha in kharif 2015 to 37.5 million ha in kharif 2016, and the sum insured increased from Rs 60,773 crore to Rs 1,08,055 crore over the same period. However, the system of crop damage assessment has not changed much and most of the states could not even procure smartphones that were supposed to facilitate the faster compilation of crop cutting experiments.”

The crisis for farmers growing pulses has a lot to do with all these schemes and their shortcomings. Unless these shortcomings are removed – especially stopping the skewing of agriculture towards rice and wheat – growing pulses will remain a very risky enterprise.

It is possible that the present crisis will have taught the government a great deal.

COMMENTS