http://www.firstpost.com/business/shift-to-cashless-here-is-how-govt-departments-may-be-misusing-e-payments-3197266.html

Epayment: when even the government begins to cheat

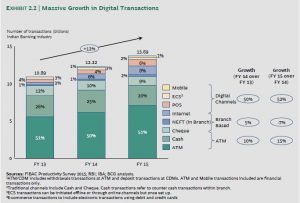

Epayment, or digital payments, are gaining popularity (see chart). The government wants to step on the gas pedal and increase the rate of acceptance of digital payment. But there are many reasons why the pace of acceptability could get stymied. One reason is that some government departments have been misusing the convenience and desirability of epayments to make fatter profits for themselves, at the cost of customer.

When a pump attendant overcharges, it is natural for a customer to get upset. But what does he do when a government itself begins to overcharge?

When a pump attendant overcharges, it is natural for a customer to get upset. But what does he do when a government itself begins to overcharge?

In some cases, the overcharging becomes blatant. That that is what happens with IRCTC. It is the largest player in the epayment segment. But it is a natural monopoly, because nobody else it permitted to sell railway tickets through the e-payment route.

And since t=railway travel is a necessity for most people, they have no option but to go through IRCTC’s portal. This organization has taken advantage of its monopoly and has begun charging a convenience fee of Rs.46 (it used to be Rs.22, but suddenly got raised to Rs.46). In addition, it reverses the transaction cost to the customer, thus not even paying the MDR (merchant discount rate) as the rest of India does. The customer swallows this, because he has no choice.

IRCTC sold around 200 million tickets during the last financial year (http://www.ibtimes.co.in/irctc-aims-earn-20-more-online-ticket-sales-fy17-677800). This translates into average ticket sales of around 5.48 lakh daily. Each ticket has to pay a flat service/convenience fee. That means that IRCTC earns around Rs.2.52 crore each day. And it does not pay MDR either. What is worse, even though the customer pays the transaction cost, this is not reflected on the receipt issued by the IRCTC. It finds reflection only on the customer’s bank statement.

Not surprisingly, the example of IRCTC has been adopted by private players like cinema malls and private airlines as well. And yet you have a government which wants to promote epayments.

Another government organization which does this is MahaVitaran (earlier known as MSEB) the monopoly electricity supplier is most parts of Maharashtra. It charges a convenience fee of 0.9% of the transaction amount, and also reverses the transaction cost to the customer. As in the case of IRCTC, the transactions costs are not included in the receipt.

Then there is the curious case of the municipal corporation of greater Mumbai (MCGM0 Try paying your water taxes online. Like with most e-commerce sites, you are asked to accept the terms and conditions laid down by MCGM. Since you don’t have much of a choice, you waive your rights to protest.

Once you log into the payment portal you discover some very interesting things. The only credit card that is accepted is American Express. No mention of RuPay, nor even Mastercard or VISA. Then go to the bank through which you want to transact payment. The list has many private banks, and ecept for SBI, shows no nationalized banks.

Try paying through any of these banks and the browser hangs after you type in your OTP. So you begin all over again.

When the transaction does get done, you find you have been billed a fee of Rs.5.75 against a Rs.111 bill which comes to a charge of 5.2%. This is higher than what Mastercard or VISA or even American Expresss charge.

This charge does not appear on the MCGM receipt. But when you examine your bank statement, you discover that the payment has been made to PayU.in. No ownership details for this portal are available on its website. However, some indication of its executive team can be found at a similar sounding site (https://corporate.payu.com/leadership-team).

Given that MCGM bills some 5 million households in Mumbai, besides billing over a million businesses for Octroi, sales tax, shops & establishment etc, the revenues PayU.in must be raking in can be substantial. Since the payment to this gateway is not given on the receipt, it is possible that none in the administration have any way of knowing how much money went to this enterprise, coutesy the MCGM.

Moreover, since entry to the website is only possible if you have a pending bill to pay, there is no way of examining how many other links lead to an aborted transaction.

There are just three instances of what government owned organizations do. The list could certainly grow longer with further investigation.

Options before the government

So what should the government do?

The first is to see if a zero charge card can become popular. But zero charge cards are possible only if the customer agrees to pay a small monthly subscription fee. It is unlikely that this will wash either with customers (or even politicians just before election time).

The second is to see if PayTM like models can proliferate, where zero transaction costs for consumers are met either through MDR receipts, or through profits earned from their merchant portal. But that will take quite some time to be set up.

The third is to use the RuPay card and get its operations subsidized by the government.

All the choices have consequences that could backfire during election season.

We need a regulator

But most critically, this sector is in need of a regulator who can decide the charges epayments can charge, and how. Today, looking at the practices of IRCTC, MSEB and MCGM, there are good reasons to ensure that the customer is not made to pay charges that do not get reflected on the bill.

The regulator would also be in charge of ensuring that there is a systems audit who can ensure that the web links to various service providers work satiusfactorily. It should not be like MCGM’s portals where all links fail, and only the one promoting a favoured gateway is allowed to work.

Finally, the regulator would also look after educating bureaucrats, customers and most importantly, the judiciary on how to understand this kind of commercial activity. Linked to this is the desperate need to set up a dispute resolution mechanism which can decide on such matters in a week’s time.

It is important for everyone to know that unlike conventional transactions where there is a paper trail, which has a long shelf life, electronic transactions have a shelf life of a few days. Unless the data is captured, and sent for forensic examination, there is a danger that it could get lost or tampered with. It would be stupid to have digital payments in a few seconds but a dispute resolution that takes years. Moreover, as most customers belong to the middle class or the economically marginalized sections, it would be cruel not to settle their dispute immediately.

Currently, there is no regulator. The RBI acts as a regulator, but its hands are full with many other activities.

It will be suicidal to promote digital payments without first working on a regulatory structure and a speedy and effective dispute resolution mechanism in place.

COMMENTS