How the Hindus lost control of their temples, gods and culture

In a landmark judgement on January 6, the Supreme Court ruled that no government had the absolute right to take over the management of temple trusts

It ruled that Article 26 of the Constitution confers certain fundamental rights upon the citizens which can neither be taken away nor abridged. The case was decided against the Tamil Nadu (TN) government which wanted to take over the management of the Chidambaram (Nataraja) temple.

This order could reopen other temple cases as well because, since Independence, state governments, with a wink and a nod from the Centre, have coveted the power and the wealth that temple trusts have enjoyed.

NT Rama Rao, former chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, ‘nationalised’ the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams or TTD (Tirupati Trusts), which administers the famous conglomeration of temples, educational and social organisations. The government of Maharashtra similarly ‘took over’ the management of important Hindu shrines like Shirdi and temples like Siddhi Vinayak.

So have many other states. The worst record is that of TN which today controls 36,425 temples, 56 mutts or religious orders (and 47 temples belonging to mutts), 1,721 specific endowments and 189 trusts.

The long-term damage such ‘takeovers’ cause has already been discussed in a column on August 19 last year. They erode the ability of a community to preserve its value system. They actually encourage ‘lumpenisation’ of the community, and later even of society.

It is anguishing to watch temples, which are at the heart of education and community development, being suppressed and thwarted from achieving their objectives by successive governments.

The insensitivity of governments is evident from the manner in which some states have tried to use temple funds to finance mid-day meal schemes. Some have tried to get trust funds to finance the building of roads and airports. Some others have tried to use temple properties as state properties to win favours or to financially benefit the privileged few.

A case in point is the Sri Kalapeshwar temple in Chennai, which gets a rental of just Rs 3,000 a month against the market rate of Rs 3 lakh. Cumulatively, the TN government claims to be earning just Rs 58 crore from rental of ‘taken over’ temple properties. Savvy lawyers have pointed out that the realisable value is over Rs 6,000 crore annually.

The difference is cause enough for a criminal investigation to be launched.

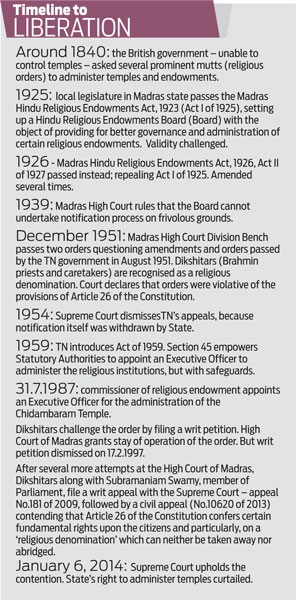

Through all these years (see box), the trusts in charge of the Chidambaram temple have refused to take such orders lying down.

Each time a new order was passed, its Brahmin caretakers, often referred to as Dikshitars, challenged it in courts. The state tried frustrating each court verdict with a new order. Finally, the matter reached the Supreme Court which reiterated that the provisions of Article 26 of the Constitution are inviolable.

referred to as Dikshitars, challenged it in courts. The state tried frustrating each court verdict with a new order. Finally, the matter reached the Supreme Court which reiterated that the provisions of Article 26 of the Constitution are inviolable.

As the court observed, “Even if the management of a temple is taken over to remedy the evil, the management must be handed over to the person concerned immediately after the evil stands remedied. Continuation thereafter would tantamount to usurpation of their proprietary rights or violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution in favour of the persons deprived. Therefore, taking over of the management in such circumstances must be for a limited period… Supercession of rights of administration cannot be of a permanent enduring nature.”

This order might go a long way in restoring to the majority community the right to govern itself. Most probably, the majority community might finally regain much of its voice and its vision.

COMMENTS